“All the people cannot be fooled all the time”

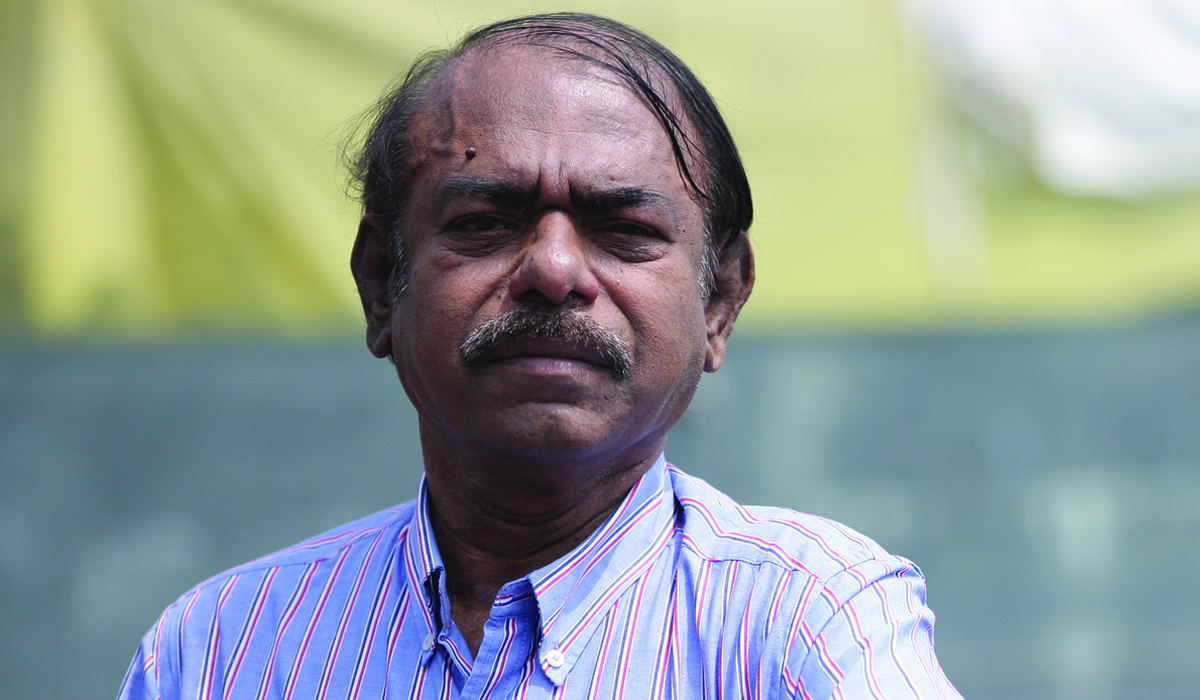

A S Panneerselvan is executive director of Panos South Asia, which fosters public debate in the region. He has been the Reader's Editor of The Hindu, and a strong advocate of ethical and responsible journalism. He teaches media studies at the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai. The following are excerpts from a recent conversation between him and Shekhar Kharel on the challenges facing old and new media.

Nepali Times: As a frequent visitor to Nepal, what do you make of the mediascape here?

A S Panneerselvan: In the 1990s Nepal set a standard for South Asian media when it came up with the finest decentralised media environment through its community radio revolution. But the digital disruption has completely changed that. While it has given a voice to everyone, no one is actually listening. We have concurrent monologues, not dialogues. There is also no supporting revenue stream for this new model.

With mobile connectivity even in rural areas, the digital divide itself is an obsolete concept. But the global media is also extremely centralised. A handful of Silicon Valley multinationals control our information ecosystem. Governments can switch off connectivity as we saw in Jammu and Kashmir in 2021 when its special status was abrogated.

Traditional media played an empowering role during Nepal’s People’s Movements I and II. But there are new questions today: Is the media going to get caught up in the social media cacophony, or play a leadership role?

How are these changes going to affect the sustainability, credibility and independence of Nepali media?

The Nepali media now has reach, but it needs revenue to survive. This is crucial because the media has a dual role: bearing witness and making sense. Bearing witness means journalists have to travel to gather news and that costs money. The budget to bear witness is shrinking. So, broadsheet publications retain their respectability by focusing more on making sense by writing editorials explaining a particular issue. Making sense has taken precedence over bearing witness. This is why the digital disruption is hurting us.

Read also: Internet in everything, Editorial

How does this revenue model then affect the digital media?

When the Arab Spring happened, we thought the digital media would become an enabler. But Trump and Brexit showed us that it is also a curse. Today, the trend is towards clickbait journalism since algorithms decide what is going to get amplified and what is not. Editorial judgment has no place in this environment, the content can be misogynist, ultra-nationalistic jingoism, war-mongering, spewing hate. It does not matter, as long as it gets the reach. When you ask Silicon Valley companies to regulate such content, they say they are not a media organisation but purely a platform. Yet they want all the credibility and reach of media organisations. When it suits them they become a media organisation, when it doesn’t they become a platform. The fact that these trans-border organisations are not governed by conventional laws is causing further harm.

The political economy of these platform companies is that they give money to the carriers, not the content generators. But carriers are not neutral. Whether they are ISP providers, DTH platforms or search engines, they are heavily loaded and discriminatory. And carriers have become so powerful that content companies are now dependent on them, and this is against the spirit of an independent media elsewhere and in Nepal.

So what is the role of journalists in this new environment?

Journalism is different from all other forms of communication because at its core is the act of verification. It is different from blogging or posts on social media with no filtration. This act of verification is mediated by editorial judgment — the two things that give journalism its credibility. Social media is destroying this and denying citizens the democratic right for credible information.

Whose responsibility is it to uphold the media’s credibility?

It is the responsibility of citizens who have to invest in credible information that is the building block of democratic rights. People’s spending on media in the last 5-10 years has gone up, but the money is going to the carriers. We pay internet service providers, DTH companies and for mobile connectivity. Money spent on those creating content for media has gone down. Credible information is a public good, we must reinvest in it.

Read also: Press for people, Sahina Shrestha

But will a public hooked on TikTok invest in credible information?

People don’t think twice about paying IPSs or for DTH connections, why would they not also pay a part of it to news outlets that they trust? Trusted institutions need a certain amount of financial leeway. Since 2006 we have witnessed a huge squeeze on the traditional media model. This is hurting us in two ways. One, the most credible information has become the most expensive, while the most salacious is the most accessible. For example in the UK, those who want credible information, say the Financial Times, have to pay, but the tabloid Daily Mail is free. Tabloidisation of news is the biggest challenge for us, and we don’t have a language to confront that. But we can’t expect the government to act either, their response is censorship. Silicon Valley corporations already account for 80% of digital revenue. If Facebook, Google and Twitter are going to take it all away, what is the role for professionals across the world working to produce credible information?

Doesn’t this erode the independence of the press?

We have to make a distinction between what was happening till 2010 and after. Until 2010, the mainstream media had its own problems, but were still largely independent. Post 2010, the ownership has gone over to big corporations who do not mind losing money as long as they prevent others from entering the field. The rules have changed in such a way that the political economy has become the corporate economy.

Read also: Digital discrimination, JB Biswokarma

So, is there a future at all for the printed media?

Digital media is here to stay, and we have to negotiate our space within this new environment. But digital platforms do not have a sustainable revenue model. We have a hybrid entity controlled by corporates, and whatever they give is what we receive. Large content generators have been reduced to an appendix. People often cite The New York Timesand the Financial Timesas examples of successful transitions, but they are only mimicking the Silicon Valley giants. The better model was that of Nepal’s community radios which decentralised credible information produced by and for the people. But even that has been eroded with corporate takeovers.

This is the year of elections in Nepal. Three Ms are considered important for the polls: Money, Muscles and Media. Are there lessons from India?

Back in the day, the media used to come up with difficult questions. Now it presents only easy answers. Social media like TikTok are leading this trend by producing content with simplified narratives which rob the reality of its complexities. The misuse of media is not new. During India’s emergency from 1975-77, the government controlled the media and yet the people eventually voted against Indira Gandhi. Recently we saw media manipulation in West Bengal, but the public voted against the BJP there. The thing is, the will of the people cannot be underestimated or manipulated beyond a point.