Kathmandu’s religious opulence

Newa community worship idols in exuberant pageantry, even though the Buddha preached humility and frugalityIt was a bitterly cold night in January 1980, and I was guarding the family's gilded Dipañkara Buddha image at Kathmandu Darbar Square.

The white palace wall was defaced with political graffiti, a sign of the anti-Panchayat street demonstrations that were going on at the time. It was also the occasion for Samyaka Mahādāna, a 12-yearly mega alms-giving Buddhist festival usually graced by the head of state.

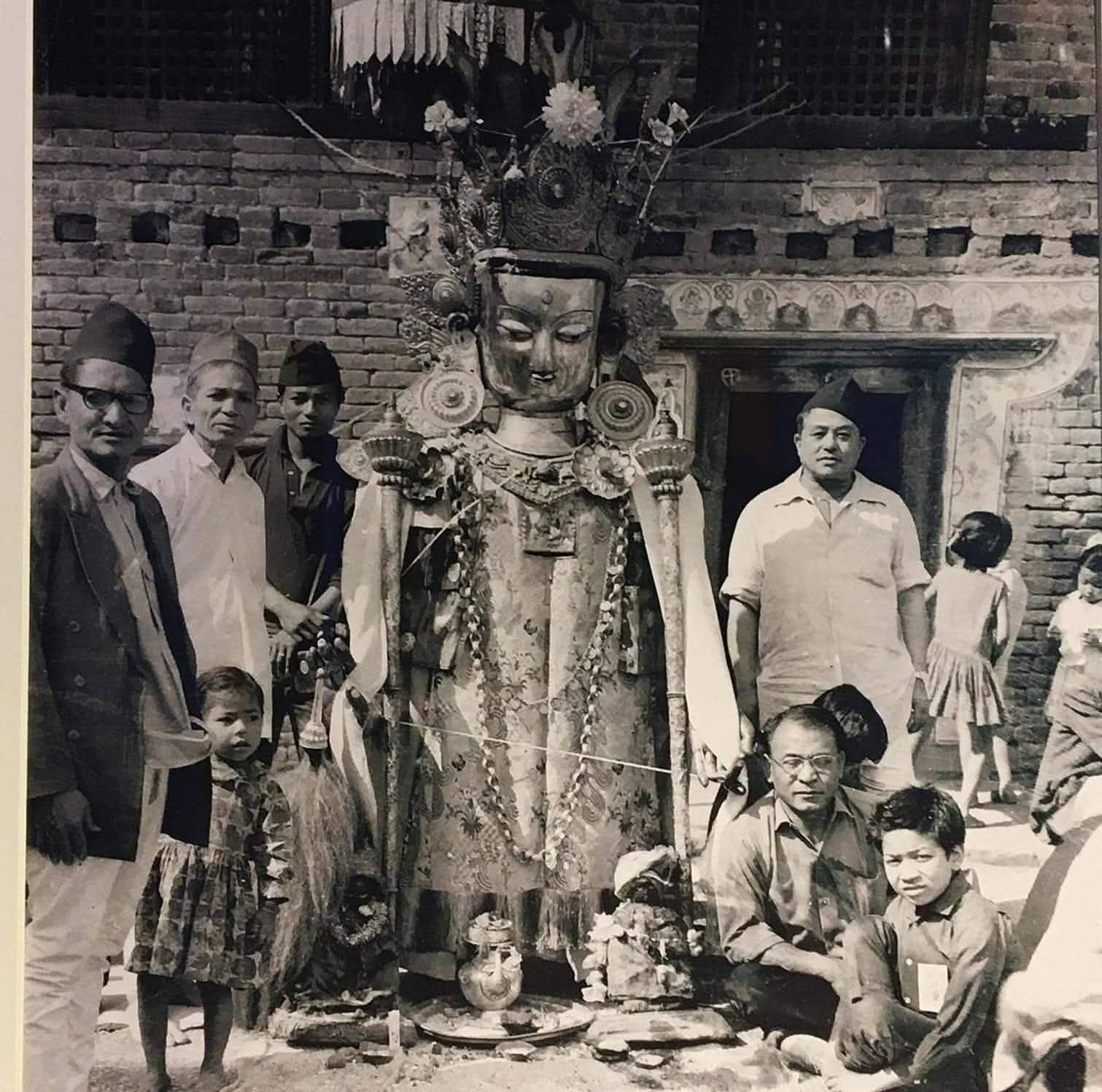

I was supposed to collect the money offered by devotees who thronged there to pay homage to Dipañkara, and the coins made a bulge in my right pocket (pictured below).

Many Newāḥ traders of Kathmāndu Valley spent some of the riches they earned from the profitable trans-Himalayan trade with Tibet organising these grand Samyaka Mahādāna festivals.

In 1882 CE, one such trader who was my ancestor, Gyān Bir Singh Tulādhar of Wonemā, had funded an exclusive Samyaka Mahādanā festival. All Newāḥ Buddhist priests in Nepāla Maṇḍala are invited to receive alms, and at the end it is obligatory for the patron to commission a large idol of Dipañkara, usually of gilded copper, with an abundance of ornaments bedecked with precious stones.

The fire-gilded statue is then consecrated so that it is elevated to the status of deity, worthy of worship. The god is handed down from generation to generation as a living testimony of one’s ancestors having paid for the elaborate Samyaka ceremony.

Succeeding generations proudly display the Dipañkara image every year along with other religious and ritualistic artefacts, such as a long, narrow scroll painting (Bilañpau) that depicts life stories of legendary figures. The exhibit is put up for several days during the holy month of Guñla, especially on the full moon and the day after, which this year fall on 9 and 10 August.

The practice of communal recitation of hymns and prayers in front of the image of Bahi Dyo, known as Tutaḥ Bwonegu, adds tranquillity and humbleness to a festival that otherwise flaunts wealth.

Entire neighbourhoods throng to pay homage to the golden Dipañkara Buddha, propped up on a wooden frame, behind latticed wooden windows in a room on the ground floor of a house in the sacred courtyard to which the family belongs.

The exhibition is known as Bahi Dyo Bwoyegu (bahi = sacred courtyard; dyo = deity; bwoyegu = to exhibit). The day after the full moon, scores of religious Dhāḥ and Khiñ drum ensembles parade around town, visiting the colourful Bahi Dyo exhibits. Bahi Dyo Bwoyegu essentially is the age-old practice of publicly showcasing the religious, artistic, and economic heritage of Newāḥ Buddhist families of Kathmandu Valley.

According to Buddhist scriptures, a Samyaka Sambuddha – an all-knowing supreme being – makes his appearance on earth after the passage of an eon. Twenty-eight such Buddhas have taken birth so far, the latest one being the Śākyamuni Gautama Buddha born in Lumbini in the 6th Century BC.

One of the earliest in the series was the Dipañkara Buddha, a great proponent of the merits of giving alms, and the one who forecast the coming of Siddhārtha Gautama, the historical Buddha.

Legend goes that while on his way to receive alms at a magnificent ceremony organised by a affluent king, Dipañkara stopped en route to receive offerings of a handful of grain from an impoverished elderly woman who had made it a habit of keeping aside a portion of her meagre income for giving away.

When asked by the puzzled king about the reason for stopping to receive such a scanty handout, Dipañkara gave a lengthy discourse about the virtue of selfless charity and the demerits of giving away riches collected by unscrupulous means. Suitably convinced, the king took up a menial job with a blacksmith, using his earnings to organise another alms giving ceremony at a later time, albeit on a much smaller scale.

This lore has been venerated to this day by the Newāḥ Buddhist community by virtuously perpetuating the tradition of giving alms on several occasions throughout the sacred month of Guñlā.

Guñlā means the month (lā) that you spend in the nearby forest (guñ) engaging in meditation and devotional activities. Also known as Varśāvās, it is the period of the annual retreat of the monsoon (Varśā = rain in Sanskrit) and coincides with the month of Śrāvan in the solar calendar when followers of Śaivism perform special prayer rituals and weekly fasts in reverence of Lord Śiva.

As part of the Guñlā celebrations, during the Pañcadāna festival all Newāḥ Buddhist households in Kāthmāndu offer alms of grain, money, and rice pudding to members of the Śakya and Bajrācārya priest clans, who go from house to house seeking alms as required by religious duty, regardless of their financial status. The Pancadāna festival is held in Pātan on the eighth day of the bright half of Śrāvan.

In line with the same philosophy, the monumental two-day alms-giving festival Samyak Mahādāna is held every 12 years in Kāthmāndu, where hundreds of Dipañkara images are paraded through the city thoroughfares and assembled at Bhuikhyaḥ, a large open public space at the base of the sacred hill of Swoyambhu.

This important event is now several years behind schedule because of the encroachment of Bhuikhyaḥ, where the alms-giving ceremony takes place. A downsized version of the Samyaka festival takes place in Pātan every five years.

Predictably enough, this display of affluence and opulence comes with its share of risks. A large gilded Dipañkara image was found missing from a reputed monastic complex in Pātan several years ago, together with many smaller images and other accessories. Later, most of the stolen items, including the Dipañkar image, surfaced at an auction house in Europe.

GODS IN SAFEKEEPING

Continuous efforts by the local community in Pātan, the Nepal government, and the ‘host’ government helped bring back the image safely to its original place of residence two years after it was stolen. But some of the pieces of the Bahi Dyo set are yet to come home.

This case has alerted other Bahi Dyo owners about the very real threat of theft, leading to many of them exhibiting the image privately in their residences only for a day or two. But while this allows for their family members to pay homage to Dipañkara, the public gets no access to them, a practice that is becoming increasingly common.

Some families have resorted to entrusting the safekeeping of the deity to one of the government museums in the city for the rest of the year after the exhibition is over.

However, some families which held the Bahi Dyo Bwoyegu ceremony privately earlier are now putting together resources and security measures to display their god openly in the courtyard for all to venerate.

Conditions governed by changing times have forced Bahi Dyo owners to adopt newer and more pragmatic practices. The Bahi Dyo Bwoyegu festival is the proudest moment of the year for communities — an opportunity to showcase the achievements of their ancestors with full religious endorsement.

This event is also a reflection of the deep devotion of the people, their uncompromising social values, and extraordinary artistic skills.

The razzmatazz of the Bahi Dyo Bwoyegu tradition may seem in sharp contrast with the merits of philanthropy preached by Dipañkara Buddha, but it has survived for centuries. In fact, this glorious intangible heritage is thriving again.

Alok Siddhi Tuladhar is a cultural preservation activist and documentary filmmaker.