Nepali workers stuck in no-man's land

More than 43,000 overseas migrant workers have returned to Nepal during the Coronavirus pandemic out of 125,000 who registered to be ‘rescued,’ according to Nepal’s Labour Ministry. The pace of the repatriation exercise has been painfully slow, and many workers who have lost their jobs or cannot bear to be so far away, are desperately trying to return home.

Many stranded workers have spent any savings that they had, and are barely surviving with support from friends, co-workers or other Nepalis, including from the Non-resident Nepali Association (NRNA). Others still do not know how they will manage to buy a ticket if they ever get on a flight list. Here are some of their stories as part of the Nepal Photo Project.

KUWAIT

Etubar Kisku went to Kuwait in 2017, encouraged by a friend from his village who was already working there. “I actually got lured into it — he painted such a rosy picture. I got excited about the idea of working at a hotel in a foreign land with a good salary. He told me that I would get 100 dinars (Rs39,000) per month. I have two daughters and a wife to look after, so I agreed.”

“When I came here things were different, I wanted to return home,” says Kisku, 36, from Bhagudubba of Jhapa district. His job was not at a hotel as promised, but in a restaurant. He was paid about Rs36,000 and was sending home Rs20,000 from it every month. But the restaurant closed, and Kisku has been without work for four months. “Thankfully the company has provided accommodation and we don’t have to pay rent,” he says.

When the pandemic started, Kisku and some of his Nepali flatmates stocked their pantry with essential items like rice, oil, salt and potatoes. He has been able to find some construction work through Indian and Bangladeshi migrant worker friends, but it is back-breaking. “The work is not regular, and for 12 hours I only make about Rs2,000,” Kisku says. “Still, it is better than having no work — it at least helps me to survive.”

He has been waiting to return home for many months, but the flight costs more than he can afford. “The ticket home is Rs85,000 one way, I don’t have that kind of money,” he says adding, “At this rate, I wonder if I will be able to go home.”

Kisku’s company still has his passport despite efforts to get it back. “I keep calling them, but they always say one thing or the other and hang up.”

Kisku has built a community of Nepalis who he calls his ‘solti’ and ‘soltini’. Every morning after waking up he calls his soltini who works at the airport to check ticket prices. “I am not educated, I do not know the ways of the world, so I ask them, and I trust that they will help me in my time of need,” he says.

- Bunu Dhungana

SAUDI ARABIA

Raju Murmu — When we talked to Raju Murmu in late August, he was crammed into a room in Saudi Arabia’s capital Jeddah with 14 other Nepalis. They had pooled their money and bought an internet package to ensure that they could tell their story to the world, but the data pack was running out, and they could not afford to buy another one.

Of the workers Murmu, 31, from Jhapa was the only one who knew how to use the internet. “Where are the concerned authorities? We want them to see the condition we are living in now, we want them to rescue us,” said Murmu then, via video call.

Murmu had been stuck in Jeddah since December. After he lost his job as a cleaner at the airport, he tried to find another one in the city, but he was not allowed to work. When the Nepal Government announced that international commercial flights would resume in August, he asked his family in Nepal to send him Rs50,000 and paid Rs84,000 for a ticket home. He also paid Rs7000 for a PCR test.

Finally on 6 September, Murmu landed in Kathmandu and quarantined in a hotel in Bag Bazar, where last Thursday he did a PCR test. He tested negative and has been with his family in Jorpati since then.

Murmu made the journey home with a heavy heart: “How can I be happy when the people I spent four years with are stuck, and have no hope of coming back? I can only be at peace when I know all my friends in Jeddah are home safe.”

- Nitu Ghale

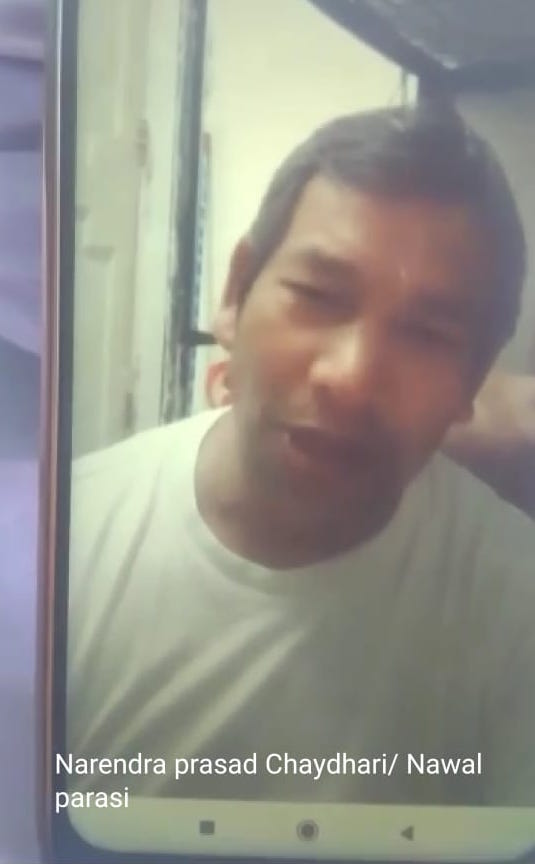

Narendra Sarwariya, Mahendra Hemran, Narendra Prasad Chaudhary, Ramnepal Thakur

Among those who shared a room with Raju Murmu are Narendra Sarwariya, 30, and Mahendra Hemran, 26, from Mahottari and Morang districts. They worked as cleaners in Jeddah but have been unemployed for the last six months.

The men have been sharing the single room with up to 14 other Nepalis. They first pooled their money and bought an internet data pack to ensure that they could share their plight. The internet ran out, and now they are selling gifts they had bought for their families — blankets, chocolates, watches, etc — to pay for the internet.

While two among them have managed to make it back to Nepal, the others whose families do not have money to send for tickets have remained behind. They are running out of food and water and have been ordered to vacate their single room. Weeks after we originally talked to Hemran, last week he left this voice message on our mobile phone: “Please help me get back home. I want to come home, I love my country. If I could come home everything would be good.”

Also sharing the room are Narendra Prasad Chaudhary, 48, from Nawalparasi and Ramnepal Thakur, 53, from Dhanusha. They cannot go home because the company they worked for refuses to return their passport.

Chaudhary says he was asked to pay Rs187,000 and Thakur Rs125,000 to get their passports back. “How can we pay such a huge amount?” asks Chaudhary. “We have been unemployed for the past six months.”

He continues: “Having worked for 12 years, I should have received a bonus. Instead, I have to give them money. And have to pay an additional amount to go home. Why do we have to pay to go home in times like these?”

- Nitu Ghale

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Raj

Raj (who asked us to hide his real name) from Bhaktapur resigned from his job in Abu Dhabi in February because he was planning to go to Croatia. However, his company did not process his resignation on time, so he got stranded in Abu Dhabi without work.

After applying twice, he got his name on the Embassy of Nepal list for a chartered flight, behind 7,000 others. In June, he trusted a friend of a friend with 1,500 dirham (Rs48,000) to book his ticket. But the agent failed to get a ticket and did not return the money.

Running out of cash, Raj, 43, started doing odd jobs like painting and moving goods to cover his basic expenses. With the help of the NRNA he got hold of the agent, who provided a small space in a room that he shared with two others, sleeping on the floor. Then the owner of the room asked him to move out or pay rent.

While he struggles to return to Nepal, at home his family is also squeezed. Raj has a son, 13, who was studying in a private school. Without any earnings the boy will have to leave that school and move to a government one.

Raj has now found a new place to stay and has a flight ticket for 22 September, which he bought for Rs79,000 after collecting small amounts from many people. As of 9 September he has about Rs6,500 left, from which Rs4,800 is for a mandatory PCR test before boarding the flight.

“I’m a very strong-willed person. I have faced difficulties in these past couple of months, but I have never given up. I was ready to go live on the streets if I had to. I took up odd jobs just so I could eat. I would not have survived if I was weak inside,” he says.

“I have not shared the hardships with my family back in Nepal. Both my parents are old and I do not want them to be stressed because of something they cannot control. I do not think my situation will change if I share it with my 80-year-old dad — what is the point?”

- Tripty Tamang Pakhrin

Kumar Shrestha

After more than five years working as a security guard in Dubai, Kumar Shrestha had hoped to clear his loans and save a little with this year’s earnings. Little did he know that he would be stuck in a camp in Al Quoz without a job from March onwards.

Things were going according to plan until January, when his company cut his salary after business declined. In March they told him to stay home until they called. Every day his roommates would leave for work while he waited for the phone to ring. “I was unemployed for six months. I was getting 300 dirham (Rs9,600) per month for food. It is not enough for an expensive city like Dubai but I do not have any other choice,” says Shrestha, 32, from Dhading.

Frustrated with the waiting, Shrestha is resigned to his fate. “I do not want to come back now. I was planning to stay for another year, pay off my bank loan, save some money and go back to my own country. The plan has been shattered by this pandemic.”

Now living with five others in a labour camp, he applied for a chartered flight from the Nepal Government but has not heard from the embassy. He planned to use his savings of Rs51,000 to buy a ticket home, but prices have risen to Rs84,000 so he cannot afford one.

He dejectedly describes his life in the camp: “I have not been in a real jail but this does feel like one … there is nothing to do and I cannot go anywhere. I am just waiting for the ticket prices to go down.”

- Tripty Tamang Pakhrin

Dipesh Bhattarai

In July, when Dipesh Bhattarai read that Nepal would resume international flights by mid-August he was thrilled. The 21-year-old has been stuck in Dubai for the last four months on an expired visa without a job, and no way to support himself. Then, his excitement turned to disappointment when the Nepal Government reversed the decision and announced that international commercial flights would remain suspended until 31 August.

Bhattarai left Bardia two years ago to support his family. In Dubai, he worked as a supply assistant. He calls the Nepal Embassy in Abu Dhabi every day but has not been bale to get through to someone with information. “The embassy doesn’t answer when people like us call," he says.

Bhattarai has no food, is running out of money and his passport is with his former employers.

“They took our passports the day we entered Dubai because they think we will run away,” he says, “this is not my country, and my country does not want me — I feel like I do not belong anywhere."

- Nitu Ghale

Krishna Bahadur Gandharva

Krishna Bahadur Gandharva, 30, from Sandhikharka of Arghakhanchi district was one of the 17 Nepalis who reached Dubai to work with Flex Facility Management in January 2020. The following month they were all left stranded, jobless. When their visas were cancelled, the company citing Covid-19 related reasons.

The group did not have money to return to Nepal. Additionally, they had borrowed from friends and banks to pay Rs140,000 each to the recruitment agency in Nepal to get their jobs. For five months, Gandharva and his friends were stuck in the Jebel Ali camp. “It was torturous. We did not have money for food, there was no running water, there was no AC and it was 55 degrees,” he says. “The NRNA gave us food once in a while, but it would only last a few days. Some days we begged for food, some days we slept without it.”

Their lives were made harder by supervisors and camp personnel who mentally and physically harassed them to try to force them to leave. Finally their employer and the Nepal Embassy reached an agreement and booked their tickets for free for 10 August. “We were so delighted to return to Nepal. I forgot all the hardships we endured during those five months the moment I heard the news,” says Gandharva.

When they reached the airport, the UAE authorities said they would charge them for overstaying their visas. “We were asked to pay 1,287 dirham (Rs41,000) each. It was a shock,” says Gandharva, adding, “we tried calling our employer but they told us to never contact them again. We had no money so we were sent back from the airport.”

The NRNA stepped in and provided them with a room in Bur Dubai, where they have been living ever since. “It’s been a month now and the NRNA has asked us to find a way to go back — the fine for living in Dubai without a visa is 25 Dirham (Rs800) per day,” says Gandharva. “Please rescue us and take us home.”

- Tripty Tamang Pakhrin

Stories produced in collaboration with @NepalPhotoProject and the Photo Circle 2020 grant.