Hotter Himalaya melts glaciers

Villages in Manang live directly below a glacial lake that is in danger of burstingThe pale green ice on the top of the lake gleams in the pale January sunlight. The dark waters beneath are visible through the translucent frozen surface.

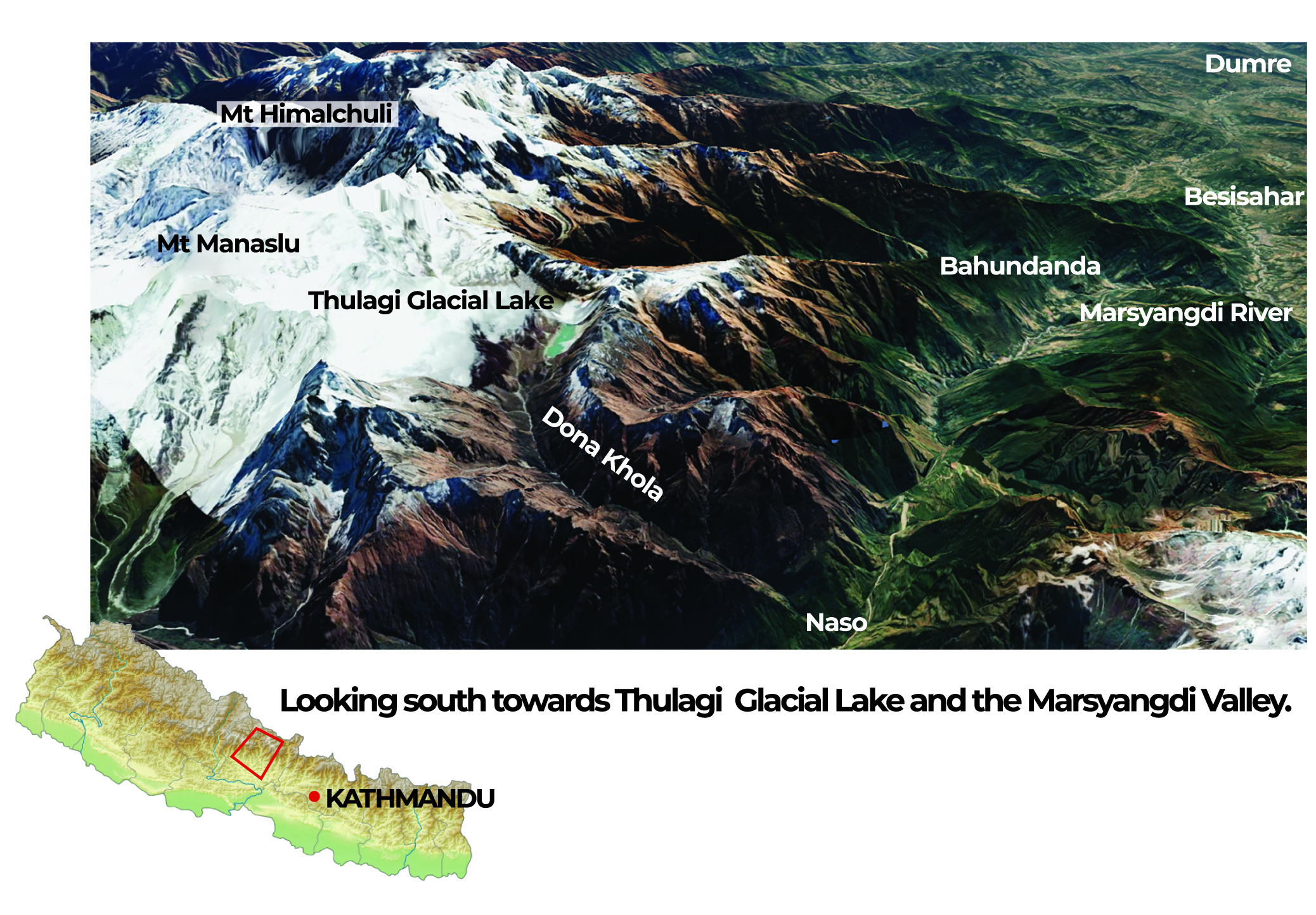

This is Thulagi Glacial Lake at the foot of Mt Manaslu in central Nepal, classified as one of the most dangerous lakes to appear in the Himalaya due to climate heating.

The place is breathtaking not just because of its 4,050m altitude, but the scenery all around. The beauty belies the threat this expanding lake poses downstream along the Marsyangdi Valley.

The lake lies at the terminus of the 4.5km long Thulagi Glacier. The local Gurung inhabitants call it Dona Tal. They say it started appearing in the 1960s. Local guide Chandra Bahadur Gurung, 47, has been ferrying trekkers to the spot for about 20 years.

“Dona used to be small, but it has now grown bigger,” he says, gesturing to how the glacier has receded and shrunk. Trekkers used to be able to go to the other side, but now the glacier is riddled with ponds and boulders falling off the moraine that make it dangerous.

Gurung adds rather matter-of-factly: “The lake will burst sooner or later.”

Kathmandu-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) has been studying Thulagi for the past two decades. Topographic maps from the 1960s and early satellite images show the lake being much smaller.

When the Marsyangdi Hydropower Project project was being built in 1994, the German Institute of Geology and Natural Resources with the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology measured the lake to be already 2km in length. More recent surveys show the lake has increased its size since then to more than 1 sq km.

The lake is among 47 dangerous glacial lakes in Nepal and Tibet identified by ICIMOD in 2020 due to its size, the risk of landslides and avalanches, and the gradual collapse of the lake’s ice-core moraine dam.

In 2018 a team of glaciologists led by Umesh K Haritasya published a journal article about the evolution of three glacial lakes including Thulagi, Lower Barun, and Imja. Even back in 1976, Thulagi was twice the size of Imja glacial lake in the Khumbu and six times the size of the Lower Barun. The team measured the lake’s depth at 79m, and calculated that it held 36.1 million m3 of water.

Since then, Thulagi has been growing at a slower rate than the other two lakes because it is shielded by shadows of mountains. There is also not as much glacial calving in the narrow valley.

Nonetheless, scientists and experts have long warned that a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) from Thulagi poses a big risk to four hydropower projects on the Marsyangdi and settlements like Besisahar and Dumre (map).

The lake feeds into Dona Khola, a tributary of the Marsyangdi where the 49.9MW Dona Khola hydropower project is being built at a cost of Rs10 billion. Another 42MW Super Dona Khola project is planned on the river.

“One of the trigger points that could lead to a glacial lake outburst could be the steep lateral moraine, which might be weakened by rapidly melting permafrost,” says Scott Watson, a University of Leeds researcher who was part of the team that conducted the 2018 study.

Locals are already witnessing what Watson describes. They say that it was easy to reach Thulagi’s headwaters even until a few years ago, but that is now dangerous because of ice and rockfalls.

GLOF WARNING

Glaciologist Rijan Bhakta Kayastha has been studying Thulagi since 1994, and was part of a team that discovered that the lake’s terminal moraine was made up of rocky soil on top and ice at its core.

In 2020, Kayastha's team published a study that modelled the route of a possible GLOF. They found that if the lake burst, it would take 2.5 hours to reach Dharapani, and 4 hours to reach Bahundanda 39km downstream.

The surge would be 13.7m high at Dharapani and 15m by the time it reached Taal, the village most at risk because it is situated only a few metres above the Marsyangdi.

‘Considering the size of the Thulagi glacial lake and its dam, it seems unlikely that a rock fall or avalanche would cause the lake to breach the moraine dam,” concluded the study. “But an earthquake or climate change would require a separate study. At present, there is no immediate or imminent threat of this glacier bursting.”

MEMORIES OF 2021

Across Manang valley, residents are haunted by the memories of the 2021 flood on the Marsyangdi that swept away parts of Chame, Dharapani, Naso, and Taal villages.

Kamarkali Gurung, grew up on the banks of the Marsyangdi in Dharapani, and had never imagined that the tranquil river she knew could become such a monster. She had saved up to build her own three-story property with 17 rooms.

Her family was away that June evening when the flood swept away her hotel. “Not even a spoon remained, everything was gone,” says Kamarkali. “Losing the hotel hurt like losing a loved one. The Marsyangdi flows through my house now, I can never go back.”

Surendra Gurung, also a hotelier, was in Dharapani the night of the flood, and can still remember the fear as the river roared towards the village. “I did not know if I would live or die,” he says.

Sirantal village was merely 10m above the Marsyangdi, and was completely destroyed by the flood. Thirty-two people were rescued by army helicopters, and most of the families have now relocated to Taal.

One of them is Singha Bahadur Gurung who also ran a lodge for 20 years. “We did not have to buy anything except rice, the soil in Sirantal was so fertile,” he remembers.

Marsyangdi now flows through where Singha Gurung’s village used to be. “Ever since the flood, I am terrified every time it rains from June to August,” he says.

The 2021 flood was during the monsoon, and was caused by unusually heavy rainfall in the catchment. A GLOF on the Marsyangdi would be much more destructive.

Roshni Ghale, 46, runs a hotel in Taal, and escaped with her family to a nearby cave as the flood engulfed nearby homes.

“We spent the next six months after the flood rebuilding our lives, going to bed hungry many a night,” she recalls. In the four years since, tourism has picked up again, but the community is still traumatised.

In the wake of the floods, the government had begun talks to rehabilitate and repatriate the community, but until now, they have been empty promises. In any case, the people here, most of them experienced hoteliers whose livelihood depends on tourism, are unwilling to uproot their lives and start over elsewhere.

DISASTER PREPAREDNESS

Even though studies have assessed the risk of GLOFs in Manang and across Nepal, and warned about the damage that such floods could cause, it took until 2021 for early warning systems to be installed on the banks of the Marsyangdi and in the town of Taal.

But beyond that, there has been little preparedness. Early warning systems and disaster preparedness are necessary not just along the Marsyangdi but also at and around Thulagi itself, say experts.

Locals here are becoming increasingly aware of the risk posed by the expanding lake up the valley, but are reluctant to leave homes and communities that they have lived in for generations. The hydropower projects on the Dona Khola promises jobs, and the local government is upgrading the hiking trail to Thulagi Lake which has become a tourist attraction.

“Manang now gets too little snow and too much rain, and the Marsyangdi charts its own course,” says Min Rashi Gurung, chair of Ward-1 of Naso rural municipality, where Thulagi is located.

But help may be on the way.Last year, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) approved a $36.1 million grant to help Nepal reduce risk of GLOFs in Thulagi and four other glacial lakes. The project is managed by the government and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

The project is set to begin next fiscal year, and will reduce the water level in the four glacial lakes including Thulagi, similar to what was done in Imja and Tso Rolpa, says Dinkar Kayastha at the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology.

Centre for Investigative Journalism - Nepal