Rasuwa flood likely a GLOF

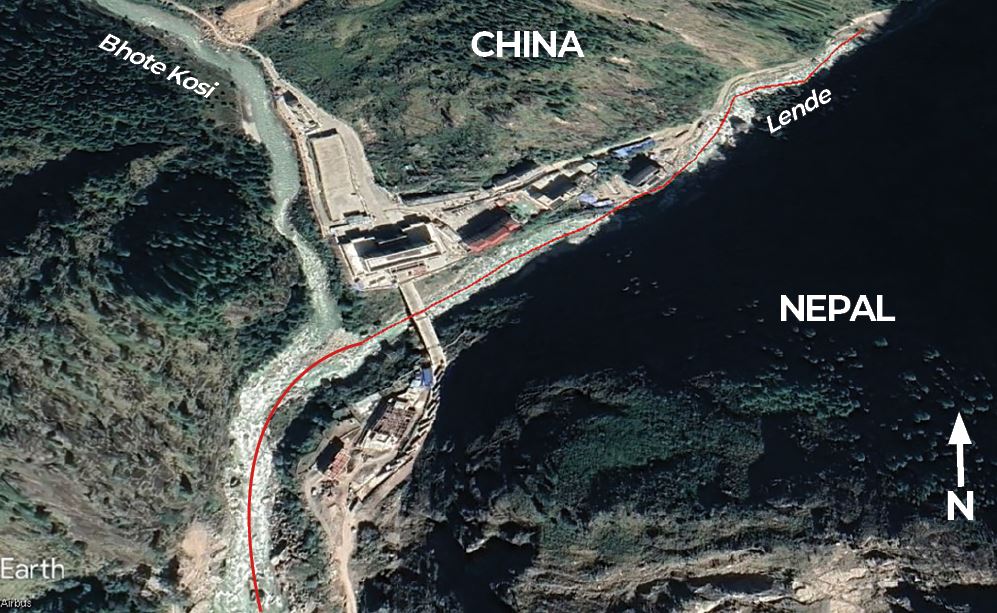

Deadly Nepal-China border flood could have been glacial lake(s) that burst in TibetThe sudden and massive flood on the Bhote Kosi early Tuesday morning washed away a strategic bridge on Nepal’s main border crossing with China for trade, tourists and pilgrims.

Slurry from the nearly 10m high debris flow left 9 dead and 20 missing, 12 of them Nepalis and six Chinese nationals, and 150 others were rescued by helicopter.

Four hydropower plants Rasuwagadi, Trisuli III, Trisuli, Benighat and the Trisuli substation sustained heavy damage, knocking out 230MW of Nepal’s power supply – approximately 8% of the total. Over 100 cargo trucks and new electric vehicles parked at Timure Dry Port were swept away.

Read also: Mapping Kangchenjung glacial flood risk, Gabe Allen

Officials had initially thought the Bhote Kosi had flooded due to heavy rain in Tibet. However, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) now say a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) is likely.

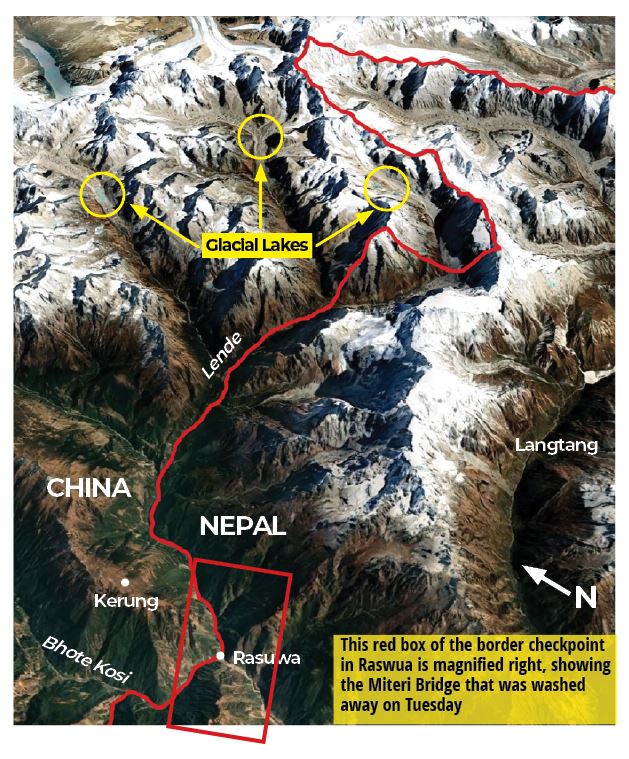

NDRRMA spokesperson Suresh Sunar said it was too early to tell which one, but the flood was most likely the result of one of the glacial lakes in Tibet. Bhote Kosi begins on the north slope of the Ganesh Himal near the Nepal-China border, and its tributary Lende drains the catchment area north of Langtang. The slurry flood on Tuesday was on the Lende (map).

“Preliminary study suggest that the disaster was not caused by rain in Tibet, but by a glacial lake burst, or another accident,” said Kamal Ram Joshi of the DHM.

The level of water at a self-monitoring station in Timure in Rasuwa increased by 3.5m at 3:10AM on Tuesday morning while 13km downstream in Syabrubesi, the level rose by 3.65m at 3:30AM. The same station recorded 5.37m ten minutes later, after which it stopped giving a reading, possibly because the station was also washed away.

The flood reached Betrawati by 5AM, and some of the debris flow reached Mugling during Tuesday. DHM’s Flood Forecasting Division noted that there was no major precipitation in the Bhote Kosi watershed in Nepal and China in the 24 hours preceding the flood.

On Wednesday, several remote-sensing experts using Copernicus satellite images pinpointed the cause of the flood to Purepu Cangbu where supraglacial ponds had merged in June to form a large lake which did not burst, but overflowed and found a channel through englacial conduits to the headwaters of the Lende. The river meets the Bhote Kosi at the Nepal-China checkpoint in Rasuwa.

“Analysis of weather forecasts and satellite data shows the Tibet region did not receive enough rain to cause this scale of flooding,” explained Binod Pokharel, associate professor of hydrology and meteorology at Tribhuvan University. “The flood could have been caused by a GLOF."

Two weeks ago, Chinese officials had reportedly warned the Rasuwa District Administration in Nepal to be on high alert for floods on rivers that originate in Tibet.

It could be that Chinese scientists had observed the alarming expansion of glacial lakes in the Lende and Bhote Kosi catchments. If that was the case, it is an example of the kind of trans-boundary forewarning that would be critical to save lives in future.

However, Rasuwa’s Assistant Chief District Officer Dhruv Prasad Adhikari seems to have no knowledge of any warning from the Chinese side, either formally or informally.

“The Chinese Embassy has said the cause of the flood is unknown that it will coordinate with Nepal to find the cause," Adhikari told us. Chinese Ambassador Chen Song and Prime Minister Oli visited the border on Tuesday (pictured).

The sharing of real-time trans-boundary rainfall and river flow data would be crucial in early warning about the risk and consequences of GLOFs to reduce human and material loss. But Nepali officials say China has been reluctant to share weather-related information and data not just in this disaster, but in the past as well.

“There is no mechanism or system in place for us to obtain hydrological and meteorological data of the Tibetan region,” said DHM Director General Joshi.

The Himalaya is melting twice as fast as the rest of the world due to a phenomenon called ‘elevation dependent warming’, and receding glaciers have led to an increasing number of transboundary GLOFs.

According to a 2018 ICIMOD study, of the 47 of the most dangerous lakes that threaten Nepal, 25 are on glaciers in China, 21 in Nepal and one in India. Many of these glaciers are expanding rapidly due to global warming.

One of the authors of the report, glacial lake expert Samjwal Bajracharya, says that the report was prepared based on data from 2015. But climate change has accelerated since then. Moreover, seismic activity has further destabilises the landscape, adding to GLOF risk.

“Considering the rapid rate of snowmelt and consequent increase in size of Himalayan glaciers, studies should be conducted every year, and a monitoring system should be set up on the glaciers,” says Bajracharya. “However, no studies have been conducted in the Himalaya in a decade, which has been our biggest weakness.”