30 years after Baby Arun

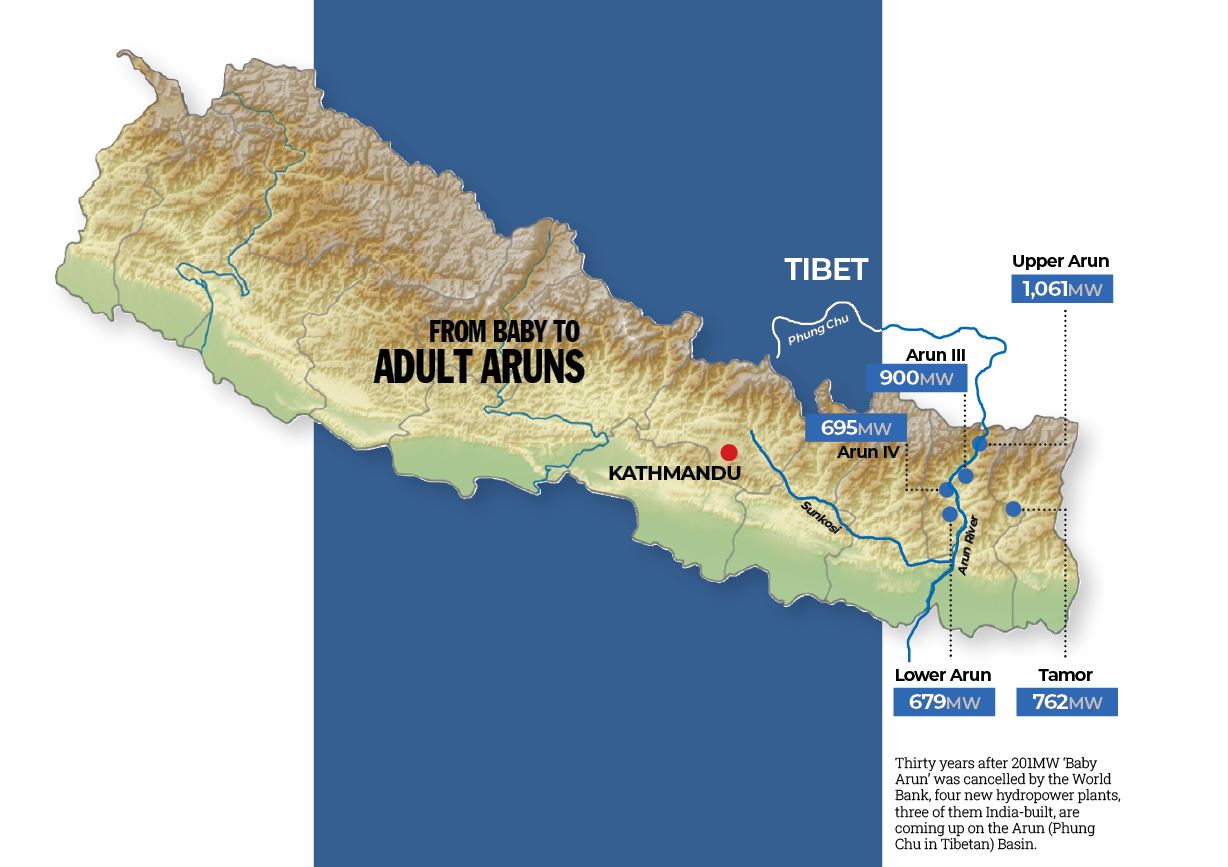

Nepal’s power sector dramatically changed direction after the cancellation of Arun III in August 1995It was 30 years ago this month that investment into ‘Baby Arun’, the 201MW first phase of the run-of-river Arun III project, was brought to a screeching halt when the World Bank officially withdrew its support.

This brought about profound and fundamental changes in the way Nepal’s power sector subsequently developed. Nepalis suffered debilitating power outages between 2008-2016 due to shortages attributable to the cancellation.

At the same time, the gap left by Baby Arun was filled by private sector investment in ways that were not obvious in 1995. It took 30 years, but in many ways Nepal’s power sector is more healthy today than it has ever been, and likely better than if the project was built as planned.

At a projected budget of $1.08 billion, Baby Arun would have cost the equivalent of Nepal’s entire annual government expenditure in 1995. It was to be funded by concessional grants and loans from multilateral and bilateral funders, including the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), KfW, and investment by the government itself.

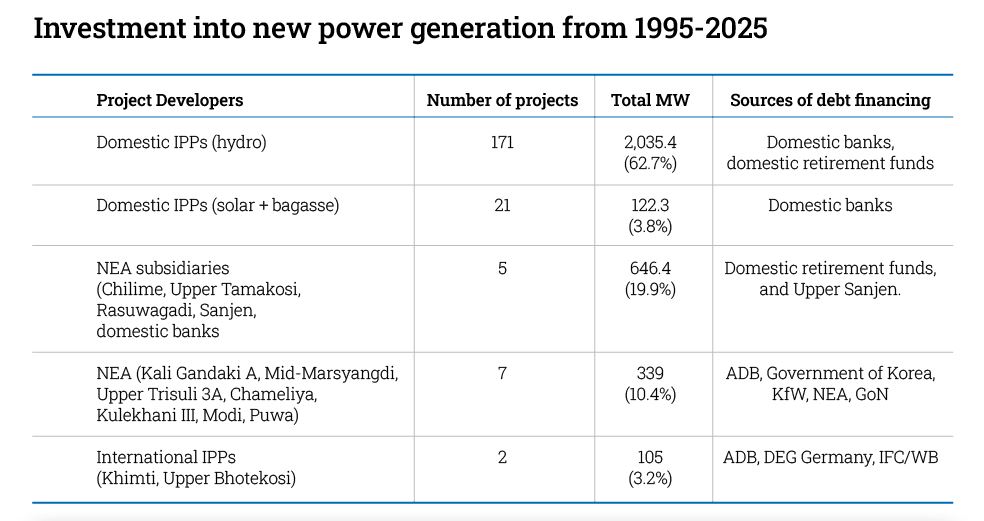

At the time, Nepal’s total electricity generation capacity was only 230MW, and the trajectory of the power sector changed dramatically following the cancellation. In the past 30 years, $5.4 billion has been invested in the power sector led by private investors, and much of it from domestic banks and pension funds (table, right).

Nearly 70% of the new megawatts generated were by private independent power producers (IPP) in the past 30 years, while the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) and its subsidiary companies added 30% of new capacity. Almost 80% of total debt financing came from domestic banks and employee retirement funds.

International assistance for power generation dropped dramatically over this time, accounting for only about 15% of investment. Before 1995 new power projects used to be entirely dependent on foreign aid. Since 1995, 63% of new generation came from 171 small hydropower projects with an average capacity of 12MW, while 4% was from 21 solar photovoltaic and biomass projects developed by local IPPs.

Over three decades, investment in Nepal’s power supply came primarily from new actors that had never before been involved in this sector. The rate of electrification rose from 10% to close to 100% -- sufficient to meet domestic needs during most of the year, and in 2024 made Nepal a net exporter of power to India for the first time in its history.

As practically all the new investment in this period went into run-of-river hydro and solar projects, rather than into hydropower reservoirs with seasonal storage, Nepal continues to rely on imports from India during the dry winter months. Surplus electricity generation for export during the monsoon is slated to grow rapidly as another 200 solar and hydro projects are nearing completion of construction, with over 5,000MW of power capacity.

Private Power

The cancellation of Baby Arun inadvertently accelerated the entry of the private sector into Nepal’s power generation. The government enacted the Electricity Act in 1992 to attract private IPPs and diversify away from total dependence from international aid, but had been struggling for several years to conclude the first agreement with the 60MW Khimti Project.

There remained a large gap between the tariff that the government thought was reasonable versus what was demanded by the Norwegian investor Statkraft, and the private sector arms of the World Bank and ADB that were financing the project.

The shock of World Bank withdrawal from Baby Arun put tremendous pressure on the government, then led by the UML as it is now. The Bank’s decision to terminate its involvement was ostensibly, at least partially, taken in response to a letter critiquing the project sent by the UML while it was in the opposition.

The government was forced to soften its position and agree to the investors’ terms following the cancellation of Baby Arun. It directed NEA to sign a power purchase agreement (PPA) with Khimti. It was concluded in January 1996, and this was followed by a second PPA in July 1996 with Panda Energy, the American developer of the 45MW Upper Bhotekosi project.

The expensive USD-denominated agreements to buy power from two international private producers, with price escalation clauses tied to the New York Consumer Price Index, sent alarm bells ringing. There was worry that the country was heading towards unaffordable tariff rates for the consumer and potential bankruptcy for NEA as a result of inevitable future weakening of the Nepali Rupee.

The government had strong-armed NEA into signing these agreements, and realised that concessionary financing terms that Nepal was used to receiving for public sector projects such as Baby Arun and Kali Gandaki A, that included below-market interest rates and 40 years repayment period with a 10 year grace period before starting repayment, were not the norm for private sector investors.

Nepal’s status as a less than attractive destination for foreign investment meant that the country had few options but to accept expensive dollar PPAs from international developers with the high commercial interest rates and short repayment periods imposed by their banks because of high investment risks.

In the end, the government ended up having to additionally provide a sovereign guarantee in order to close the deal at the insistence of the lenders – committing it to repayment in case NEA defaulted on paying the IPPs. It is reasonable to assume that the extraordinarily high political cost of agreeing to the PPA terms would have meant that no government would have willingly agreed to them in 1995 had it not suffered the trauma of the loss of concessionary-financed public sector projects as large as the Baby Arun.

It has taken NEA 25 years to consider offering dollar-denominated PPAs again: to cover the foreign exchange portion of the investment in the 216MW Upper Trisuli-1 and 120MW Rasuwa-Bhotekosi Hydropower projects. It seemed unlikely at the time, but it turned out that the dire situation Nepal found itself in 1995 planted the seed to mobilise investment for affordable power from within the country.

Double Whammy

After the dual shock of first losing investment in Baby Arun and having to sign expensive power purchase agreements with international IPPs, the first proposal for an alternative strategy to mitigate the risk of foreign currency investment into hydropower projects came from a group of engineers within the Arun III team at NEA.

Led by Deputy Director Damber Bahadur Nepali, engineers convinced the leadership that NEA needed to invest in a subsidiary company to build a series of locally-designed and domestically-financed projects that would have lower cost with rupee-denominated PPAs.

They registered the Chilime Hydropower Company Limited (CHCL) in October 1995 with 51% shares from NEA, 25% from its employees, and 24% available for the general public, 10% of which was prioritised for local residents at the project site.

The 22.1MW project is in Rasuwa on a tributary of the Trisuli, and mobilised debt financing from the Employee Provident Fund, which manages retirement savings for employees of the government, public enterprises, and private sector institutions.

CHCL’s experience showed that NEA employees themselves believed that individual hydropower projects with operational independence from NEA could be developed profitably in Nepal by its own engineers -- and they were willing to put their own money on the line. Chilime also demonstrated that there was money in the country, particularly with retirement funds, looking for opportunities for long-term investments.

Following completion of Chilime in 2003, CHCL led the formation of three other NEA subsidiary companies that completed construction in 2023 and 2024, producing 168.3MW using fully rupee-tied investment. NEA’s largest subsidiary, the Upper Tamakosi Hydropower Limited, completed construction of its 456MW plant in 2021.

There were some delays and cost overruns on this run-of-river project, the largest in the country with a final cost of over $700 million -- all of it sourced domestically. The five subsidiary companies launched by NEA have produced almost two times as much new power as NEA has over the past 30 years.

Seven other NEA subsidiaries are currently constructing projects to add another 474MW to the national grid. But even more important than NEA subsidiaries have been local IPPs: Nepali companies which have over the past three decades enthusiastically entered the hydropower sector.

From a regulatory perspective, the credit for mobilising domestic private investment to engage in power generation goes to Minister of Water Resources Shailaja Acharya, who in 1998 offered a flat feed-in-tariff of Rs4/kWh for hydropower projects under 10MW.

This upfront offer removed a major barrier that early developers had faced of having to spend money to carry out a detailed feasibility study before they could even start tariff negotiations with NEA. She had laid the foundation stone of the Chilime project, and proved to be the champion of opening up the sector for domestic IPPs.

The guarantee of a PPA with a fixed tariff, irrespective of project specifications, gave small power developers the confidence to apply for survey licenses and invest in feasibility studies so they could directly approach commercial banks and make a case for their project producing required revenue to repay loans.

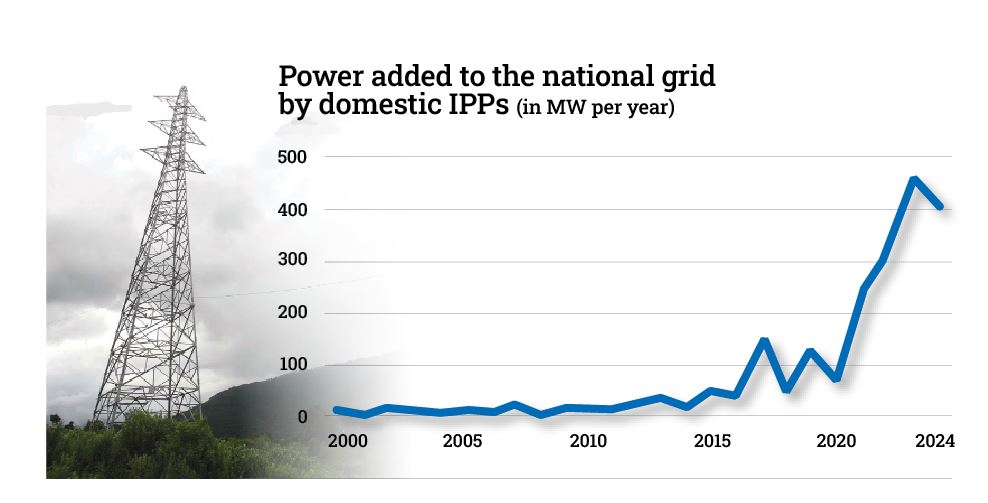

Domestic IPPs started adding power to the national grid in 2002. Their contribution was initially modest, and first projects were small and commercial lenders who took time to be confident about providing debt financing to a sector which had previously not been considered suitable for private sector investment.

While the first 10 years were slow, with less than 10MW being added to the grid each year, this increased twenty fold over the following ten years, resulting in the equivalent of a Baby Arun being added by Nepali IPPs to the grid each year. A total of 84 IPPs added 232MW, 328 MW, 454MW, and 400MW of new generation to the grid in 2021-2024 (graph). There was explosive, exponential growth as domestic developers have surged ahead to account for 76% of the new megawatts added to the grid since 2020, compared to 24% by NEA and its subsidiary companies.

The megawatts that IPPs are adding have followed the classic ‘hockey stick curve’ with the ‘breakout point’, signaling the rapid growth phase in 2020. Private producers are expected to accelerate new generation in the coming years with 300 solar and hydropower projects adding 11,000MW. Another 166 hydropower and 96 solar projects are currently in the survey stage, and are in line to add another 11,000MW to the construction pipeline.

One major challenge is finding financing required for the projects. Domestic investment will no longer be sufficient to finance this ambitious pipeline of renewable energy projects. Project developers as well as NEA and the Electricity Regulatory Commission will have to leverage their substantial experience accumulated through the construction of over 200 projects to attract regional and international investment and hedge the risks of dollar-denominated PPAs.

Following the cancellation of Baby Arun, Nepal developed a highly distributed power sector. The national electricity grid is currently supplied with power from a remarkably decentralised array of hundreds of hydropower and solar photovoltaic projects spread across 43 districts and all seven provinces.

This presents a sharp contrast to the pathway of a few large public sector hydropower projects with a sprinkling of private sector projects that was envisioned as part of NEA’s investment planning when Baby Arun was being considered the front runner for investment. The strategy then was to allow public sector investment in a few large hydropower projects with thermal plants to fill the gap. Knowing what we know now about acceleration of climate change impacts and increased extreme weather events, following this path would have made Nepal’s power sector highly vulnerable.

Decentralised generation greatly improves the resilience of Nepal’s power supply as damage to power plants in one part of the country need not affect other areas that have their own generation. Following the investment plan where over two thirds of the country’s power supply would have come from power plants on the Arun River, would have greatly imperiled Nepal’s energy security.

All rivers in Nepal are susceptible to flooding from cloudbursts made more frequent by climate change. The Arun River which is fed by glaciers in Tibet is also at risk to glacial lake outburst floods.

Bikash Pandey is Director of Clean Energy and Circular Economy at Winrock International. People Power is his regular column in Nepali Times on global energy issues relevant to Nepal.

Decentralised and Diversified

In the 30 years since the cancellation of ‘Baby Arun’:

Hydropower projects constructed cover capacities ranging from less than 1MW to 456MW and developed by IPPs from across the country with strong local involvement in purchasing equity shares.

Renewable energy sources contributed to the generation mix through solar IPPs that further contribute to climate resilience, and cover shortfalls during low rainfall. The government is committed to solar contributing 10% of the power on the grid. Increasing solar beyond this target and providing incentives to project developers to invest in utility-scale battery storage would further improve resilience.

BIG ARUN: The 900MW Arun III project under construction since 2018 at Num in Sankhuwasabha (pictured, below) is a separate initiative by a different project developer using a different financing modality. The ‘Baby Arun’ version of Arun III was cancelled in 1995.