Defying predictions, Nepal’s remittances still high

Despite dire predictions about a drastic drop in remittances that Nepal gets from its workers abroad due to the Covid-19 induced economic downturn, money transfers have hit Rs875 billion which is only 0.5% less than the preceding year.

This is in stark contrast to the World Bank’s prediction of a 14% decline, a worst-case scenario of a 28.7% drop by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the forecast of an 18% reduction by Nepal’s Central Bureau of Statistics.

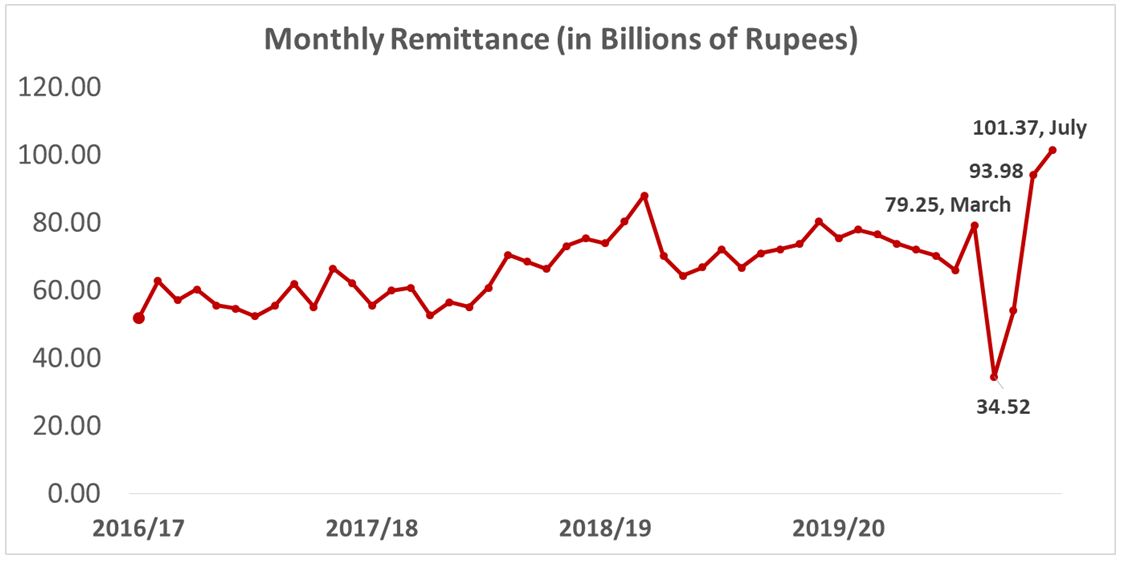

During the initial months of the crisis in March/April remittances did take a sharp dip, declining from Rs79.2 billion the preceding month to Rs34.5 billion. But it has since picked up, rising steadily to Rs94 billion in May/June and Rs101 billion in June/July. Far from declining, the figures for the past two months are record high monthly inflows to date. (See graphs)

The annual growth rate of remittances till this year, which declined by only 0.5%, had been on a positive trajectory, with year-on-year increase of 7.9% in 2017/18 and 14.1% in 2018/19.

“In many essential sectors including manufacturing, Nepali migrant workers overseas have continued to work throughout the pandemic,” explains Gunakar Bhatta, spokesperson at Nepal Rastra Bank. With news of the virus spreading in Nepal and complications with repatriation, many workers may now be weighing their options and deciding to stay back abroad.

Ramesh, a Nepali worker at WRP Asia, a company making latex gloves in Malaysia, says that after the initial slump at the factory, there is now lots of work because of the heightened global demand for gloves.

“We are now all working overtime. I just finished an 11 hour shift, 8 hours of my regular hours with 3 hours overtime,” he told us over the phone from Kuala Lumpur. Other Nepalis employed overseas in storekeeping, domestic work, cleaning and security, considered essential services, have continued to work right through the pandemic.

Also, the volume of workers who have registered to return home pales in comparison those who have decided to stay back, either because they are continuing to work or they are in a wait-and-watch mode as their decision depends on the situation of their employers. Many are also waiting for normal flights to resume on 1 September.

Ram, a Nepali worker in Qatar, says he holds his transfers when the banks are closed back home, but the pandemic has not stopped the monthly remittances to family in Nepal. “I send money home very month, just like I did before Covid-19, things have not changed much for me or my family. I use my bank phone app to transfer the money,” he says.

At the central bank, Gunakar Bhatta notes that contrary to initial fears, China’s demand for oil has recovered to over 90% of pre-pandemic levels, which bodes well for Gulf economies and subsequent demand for migrant workers.

This trend is mixed in other labour-sending countries in the region. Both Pakistan and Bangladesh have seen a surge in remittances, whereas the Phillipines has seen a decline. Some experts say the increase in the past two months in Nepal may be due to workers sending more money home to their families because their incomes have been affected by the lockdowns. The higher June-July figures could also be because of the backlog from earlier months of the lockdown.

“Migrants may have sent what is remaining of their savings from their bank accounts and their gratuity if any. It is uncertain what the numbers will look like next fiscal year, remittance data for August will be a helpful indication,” says Suman Pokharel, CEO of International Money Express (IME).

He adds that the decrease in economic activity and the disruptions in travel have led to a drop in informal hundi transfers, and an increase in transactions through banks and registered money transfer agencies.

The Nepali rupee-US dollar exchange rate is at an all-time low of about Rs120, and in dollar terms total remittances this year have decreased by 3.3%, and in 2018/19 it had actually increased by 7.8%.

The outflow of overseas migrant workers decreased in 2019/20 compared to the previous year after the government stopped issuing labour approvals from the third week of March. In 2018/19, 236,208 new workers had left for foreign employment, and 272,616 migrants renewed their permits. This year, that number has decreased to 190,453 and 177,980 respectively (See graph).

Remittances in 2020/21 could therefore take a hit due to the reduction in both the flow and stock of workers due to shrinking demand and job displacements, or contract completion.

While the remittances this year have defied predictions, it masks individual stories of many migrant workers who have not only been unable to send remittances home, but are living in charity and desperate to return. Many are stranded due to uncertain and inadequate repatriation flights, the government’s constant flip-flopping in decisions, and lack of communication.

The Rs875 billion that was remitted this year will cushion to Nepal’s economy, and also includes contributions from undocumented workers who send home money regularly. However, these workers are not eligible for the government’s repatriation support scheme for tickets and quarantine back home which is funded by the Foreign Employment Welfare Fund (FEWF). Nor has an alternate mechanism mobilising the government’s Covid-19 fund been set up to support them.

writer