COVID-19 impact on food and school in Nepali children

A survey of Nepal’s children during the lockdown has confirmed what experts had feared – that there has been an adverse impact on education and nutrition for a majority of them.

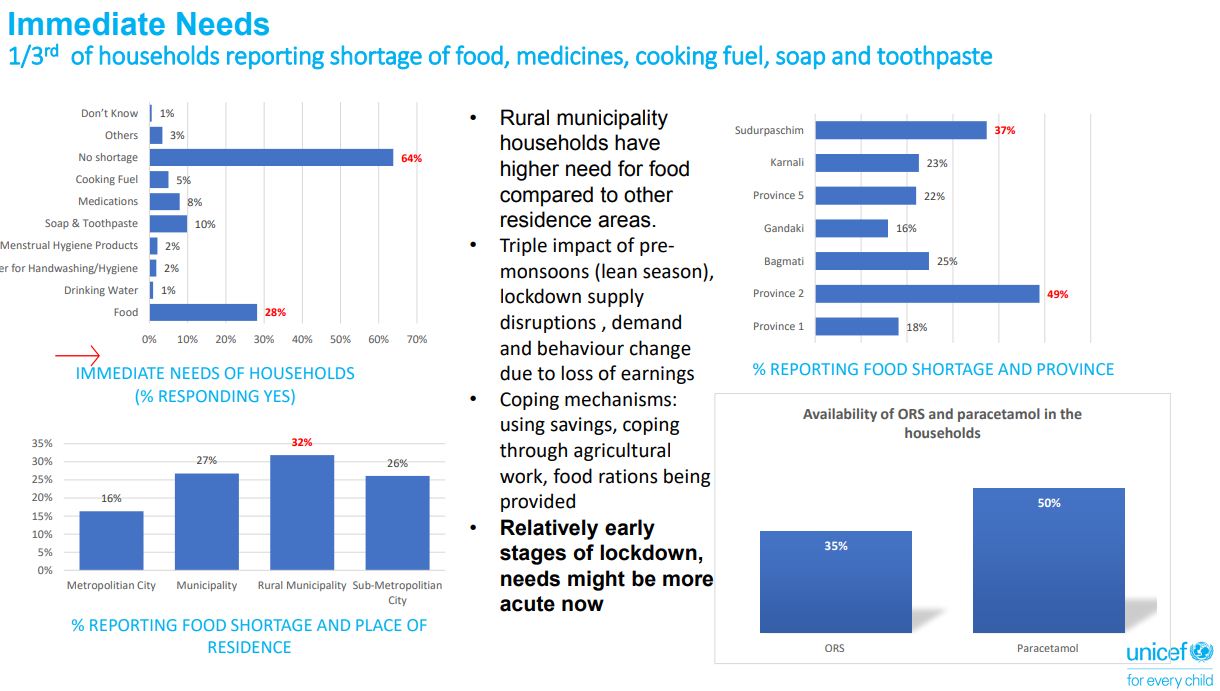

More than half the families polled reported a loss of jobs or earnings, and this resulted in one-third of the households facing shortages of food, medicines and other necessities.

This has impacted children within those households most directly, according to the first of a monthly tracking poll conducted nationwide by UNICEF Nepal and Sharecast Initiative at the end of May.

Because more than two months have passed since the poll was taken, the situation for Nepal’s children is likely to be even more precarious. Some 7,500 households with at least one child was covered in the survey – more than 70% of them engaged in agriculture and a quarter with salaried jobs.

Province 2 reported the highest rates (77%) of job and earnings losses, and those whose incomes were most affected by the COVID-19 lockdown lived in sub-metropolitan cities. People living in big cities and in Gandaki Province were less affected by the lockdown.

This is sure to mean that the pandemic and the lockdown is widening already skewed income disparities within Nepal. Those earning less than Rs20,000 a month were the ones whose livelihoods have been most adversely impacted by the impact of the pandemic on the economy.

Households facing the brunt of this income loss reported shortages of food, medicines, fuel and other essentials. Since the survey was conducted in May, many households were already low on food, and there were supply chain disruptions. Remittances from Nepali abroad fell by half in April, compared to the same month last year.

“The survey was done in the early stages of the lockdown, so we expect the impact to be greater now,” says Madhu Acharya of Sharecast Initiative that conducted the survey.

Although 64% of those surveyed said they were not suffering any shortages, rural respondents in Sudurpaschim and Province 2 reported the most food shortages. The shortages were manifested in families not being able to afford meat, eggs, dairy products, and some vegetables. This is expected to increase malnutrition among Nepali children under five, 43% of whom were already malnourished.

More than half the children in Karnali Province are stunted because of insufficient nutrition. Many of the most vulnerable children who were getting in school meals have not been able to go to school for the past five months and have been missing out on supplemental nutrition.

One in every five household polled in the survey in May said their children were getting a reduced variety and smaller portions in fewer meals. Understandably, the reduction in food intake was highest in households with lowest incomes – one-third of them said their children were getting less food.

Some 18% of mothers said they were breastfeeding more to compensate for reduced food intake of their small children, with the numbers much higher (32-34%) in Sudurpaschim and Karnali Provinces.

Some 16% of breasting mothers of children under two from the poorest families reported that they were eating less, even though 90% of Nepali mothers said they were breastfeeding their children.

UNICEF says that although some of these changes could be related to existing pre-monsoon shortages, it warns that the response of households to reduce food intake in children is worrying.

The survey shows that in May most families had been coping by digging into their savings (better off families), or by borrowing money from friends and relatives (poorer households).

Preliminery government statistics show that there has been a 30% increase in the number of under-fives who have died in the March-April-June this year compared to the same three months last year – mainly due lack of transport to take sick children to hospital, or reluctance to seek medical attention because of the fear of the virus.

The survey found that although 83% of pregnant women had access to ante-natal care, the figure was much lower for Province 2 (74%). Disaggregating that data by ethnicity, it was found that only half the Tarai Brahmin mothers polled had health checkups during their pregnancy in May. Surprisingly, the figure for Tarai Dalits was a much higher 77%.

Perhaps the most serious impact of the lockdown has been on education. Even in May, 95% of households said their children had stopped going to school, and 52% were not even studying at home. Only 29% had access to distance learning, but that only half were using it.

That means only about 12% of Nepali children are taking classes online, or through radio/tv. Even here, the disparity is stark: while up to a third of children in higher income households were using distance learning tools, only 5% in poorer families were doing so.

“The continued loss of access to education in low income families might have irreversible negative effects on the country’s economy and adversely affect the potential of the country to ensure equitable and sustainable development,” UNICEF concludes.

The more positive aspect of the survey results is that there is high level of awareness about the way in which COVID-19 is transmitted, and most families appeared to be taking the necessary precautions.

More than 93% knew how the coronavirus spread, what preventive measures to take and most said they were washing hands frequently with soap, staying at home, and wearing masks when outside. This means preventive measures against SARS-CoV-2 could also protect Nepalis from other prevalent infections like diarrhea, typhoid, tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases.

The household members told enumerators they got most of their information about the disease from radio (82%), from family and friends (72%), mobile ring tone (38%) and ward officials.

More results of the UNICEF-Sharecast report here.