Nepal’s unchanging domestic worker saga

On 30th July, World Day against Trafficking in Persons, Nepali Times’ coverage of migration in the last 25 yearsNepali Times celebrated its 25th anniversary on 25 July, and this piqued my curiosity about how the paper covered migration in the early days. Things must have been so different back then. Or were they?

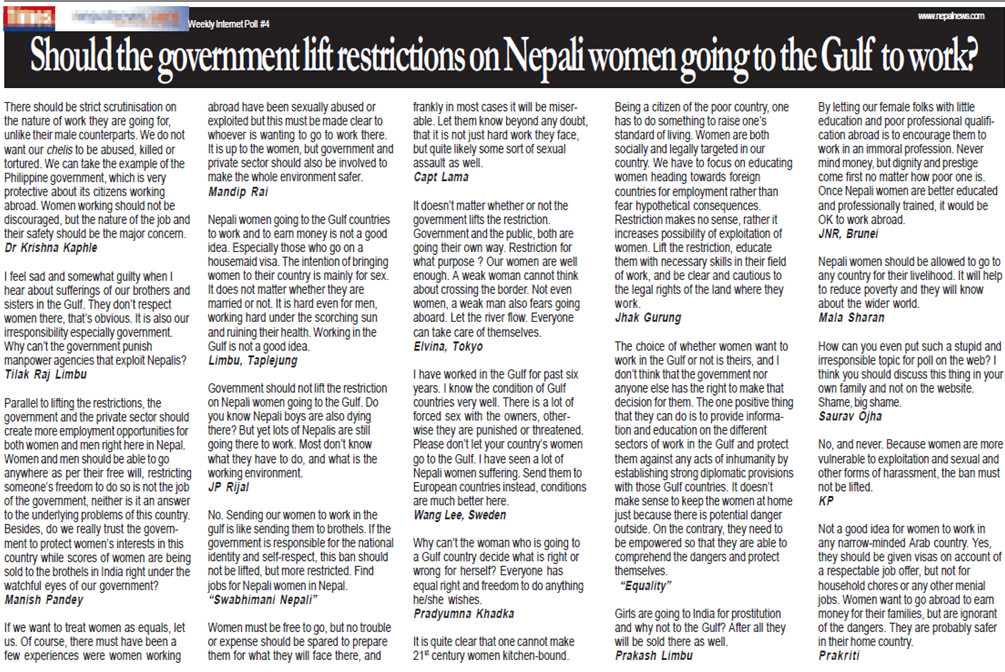

If we look at restrictive emigration policies that disproportionately impact women, contributors have changed, protagonists have changed, but the message remains more or less the same. Many aspects of what we write today about bans are no different from what was written back then, and it is timely to revisit this issue today on World Day Against Trafficking in Persons.

Trafficking can only be addressed when people have access to safe and legal migration pathways, not with bans.

In an article in 2000, the year this paper was born, correspondent Hemlata Rai wrote an article called ‘Misplaced Chivalry’ that criticised the ban on women migration. Back then, it was not a ban on just domestic work but on women migration altogether.

Excerpt from the article:

What the prohibition has done is make women more vulnerable to economic and sexual exploitation. Since the women now use illegal channels to reach their destinations, they remain invisible in official books and therefore unprotected by laws that ensure workers’ rights…. The government has simply not been able to put an end to this trafficking, and by its across-the-board ban on women workers going to the Gulf has only succeeded in pushing an employment channel underground.

Twenty-five years later, I could just reuse this paragraph, and it would still be relevant, albeit the current ban is on domestic work that disproportionately impacts women and not all women migrants.

In a 2003 news piece, there was a hopeful government announcement that the ban on women working in Gulf countries was lifted, provided a recruiter and embassy could guarantee safe working conditions, after ‘activists criticised the restriction as discriminatory’.

In 2006, Dambar Shrestha noted that the remaining restriction on women migrating to the Gulf for domestic work would also likely be repealed after the introduction of the Foreign Employment Act in 2007:

‘There was a general consensus (among Government and advocates) that the ban should be repealed, as a way to monitor overseas employment, and ensure women have legal recourse if mistreated.’

Indeed, the ban was lifted but its aftermath. Mallika Aryal’s 2009 article ‘The Invisible’ and Rubeena Mahato’s ‘Womanpower’ noted that women still struggled to migrate because of the bureaucratic challenges:

‘Despite being legally allowed to go abroad to work, government rules make it as difficult as possible for them to do so.’ (Mallika Aryal) or because of the perception of the ban, ‘After the Foreign Employment Act 2007 was passed, the ban has officially been lifted, and there are no restrictions on women migrant workers going abroad. But the perception of a ban remains, and this has led many women to continue using illegal routes.’

By the time people become aware that bans have been lifted or get a grasp of how to navigate the post-ban recruitment system, another iteration of the ban is introduced whether it is conditional (age-specific, country-specific) or blanket bans bringing us back to square 1.

See the flipflopping I attempted to trace in a 2021 article, History of Female Im-mobility in Nepal. Just like the ban is a reactionary policy, this article was a reaction to a bizarre proposal to require consent from a guardian and local government for women under the age of 40 travelling to the Gulf or Africa which fortunately got quashed.

But bans don’t work, have never worked, given irregular options via open borders and visit visas, as has been extensively covered in this paper since its first year. The latest ban, imposed in 2017 after a Parliamentary committee visited the Gulf and decided it was unsafe for domestic workers, regardless of gender.

Any promise for change such as a 2020 Parliamentary trip after which the committee instructed the government to revisit the ban considering country-specific policies and several preconditions, which were still deemed restrictive, has stalled. A proposal around lifting the ban starting with a pilot agreement with the UAE submitted by the Labour Ministry has also stalled.

One would think that 25 years is a long enough time horizon for progress that would bring us to a point where we would look back and gasp at how bans were imposed to curb migration that disproportionately impacted women.

What on earth was the Government thinking, we could have wondered? On the contrary, this is still our reality and we are in fact in the midst of a fresh, high profile visit visa scandal that has become a core public contention issue. The misuse of visit visas is inevitably linked to deployment bans and profit motives.

These scandals cast doubt on the claim that the bans are really for ‘protection’ of women. To be sure, domestic work remains one of the most vulnerable sectors with women disproportionately affected. Excessive working hours, payment issues such as non-payment or underpayment, verbal, physical and even sexual abuse are prevalent.

Countries including in the Middle East have increasingly adopted regulations protecting women but there are severe limits in both the protections they offer or their implementation. These abuses are very much present, prevalent and cannot be ignored.

But Nepal has not taken the steps to proactively address these issues because the bans alone take centre focus despite their ineffectiveness. The restrictive policy has not been overhauled despite decades of progress since Hemlata Rai first reported on this subject in this paper in terms of better databases for recordkeeping, stronger international conventions, laws and standards governing this sector, better developed curricula on domestic work, stronger regulations for recruiters deploying domestic workers, social media that keeps domestic workers connected.

There are developments from the last two decades that can be utilized to make the sector safer should there be a willingness to do so. Because the reality is, these opportunities are life-changing for many migrants and their families.

If and when we get to celebrate the lifting of the ban, it will be just that: a celebration of the ban being lifted, which is not a lot to begin with. A low bar. Because it will only clear the way to begin real work to tangibly make this sector safe.

What is needed past the ban will be a lot of work: stronger embassies, better recordkeeping, enforceable bilateral labour agreements, monitoring, pre-departure training and awareness campaigns. Perhaps that is another reason why there is such slow progress because imposing a ban does give the semblance of doing something in the name of protection without really doing much?

Twenty-five years of reporting in Nepali Times on bans on women migrant workers has one lesson: they still don’t work -- just as the paper reported back in 2000.

In this spirit of lazy policymaking and the lackluster progress on addressing deployment bans, here are five endings from previous articles covered in the paper on this issue. Please choose as per your liking;

‘The government has simply not been able to put an end to this trafficking, and by its across-the-board ban on women workers going to the Gulf has only succeeded in pushing an employment channel underground.’ (Hemlata Rai, 2000)

‘How can the government be so apathetic towards this problem when women make such a significant contribution to the national economy?’ (Dewan Rai, 2009)

‘Unless the government is serious about enforcing the provisions of the Foreign Employment Act and creates a safety net for migrant workers, these statistics and the lives of countless Nepali women will only get worse.’ (Sushila Budhathoki and Mina Sharma, 2012)

‘The ban needs to be lifted, but this is also an opportune moment to address other less-explicit but enduring factors that are holding women back, both literally and figuratively.’ (Upasana Khadka, 2020)

‘Undocumented domestic workers are citizens too, and it is the duty of the state not to abandon them.’ (Ayushman Bhagat and Sunita Mainali, 2025)

Upasana Khadka heads Migration Lab, a social enterprise aimed at making migration outcomes better for workers and their families. Labour Mobility is a regular column in Nepali Times.

writer