Parks by the people and for the people

Buffer zone governance committees have made national parks participatory, but not inclusiveDimar Chaudhary was born and raised in Old Padampur, the village inside what is now Chitwan National Park before it was dsignated a protected area.

His Tharu community, as well as other indigenous groups, traditionally relied on Chitwan’s jungles and rivers for generations. Chaudhary himself had grown up collecting medicinal plants and wild vegetables, gathering wood, and grazing cattle in the forest.

Chitwan, along with much of Nepal’s Tarai, was plagued by malaria until a US-supported DDT spraying campaign to wipe out the disease in the district in the 1950s. This opened the valley up to trans-migration of farmers from the hills. Before that, Chitwan was inhabited entirely by indigenous people: 90% of the district’s population was Tharu, and the rest were Bote, Mushar, Darai and Majhi communities.

In 1973 Chitwan National Park became Nepal's first protected area and in 1996, the Nepal government introduced the Buffer Zone Management Rule under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act to manage forests surrounding protected areas, and ensure local participation in parks management.

Old Padampur was subsequently relocated outside the park. Ntional parks formed buffer zone user committees (BZUCs) to manage and oversee community forests. Hundreds of thousands of local people were directly involved in managing buffer zone community forests across the country.

Over three decades, these forests have not only made conservation collaborative, but also helped to mitigate wildlife-related crimes and human wildlife conflict. In 2014, 2015 and 2016, Nepal achieved zero poaching for its three flagship species: rhinos, tigers and elephants.

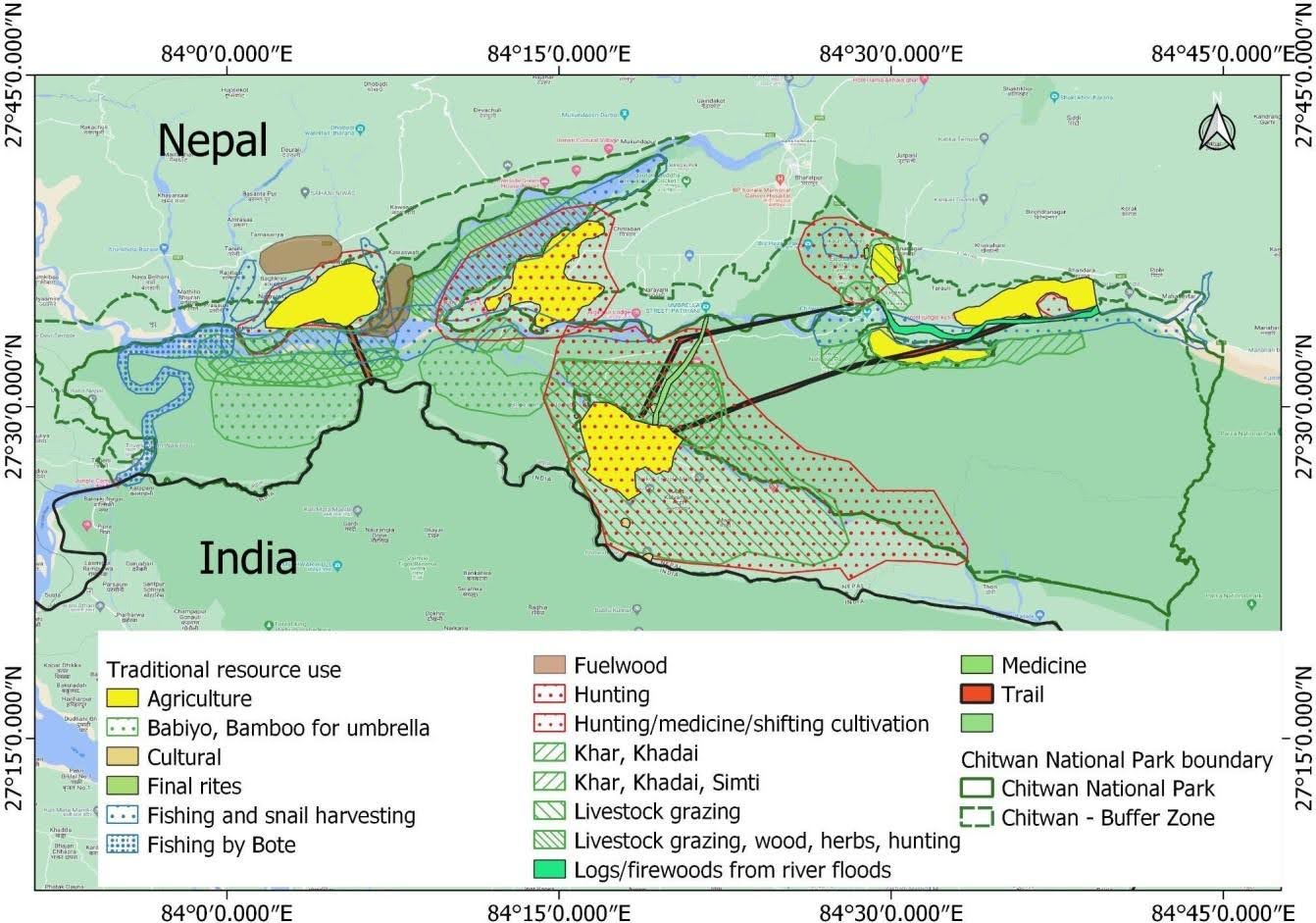

But while these user communities have made wildlife conservation participatory, the process hasn’t been inclusive of Nepal’s indigenous and underserved communities. In 2022, WWF supported Community Conservation Nepal to collect data on natural resources used by Tharu indigenous people before the establishment of Chitwan National Park.

The project also looked into the inclusion of indigenous, women, Dalit and disabled communities in the Baghauda, Paachpandav, Meghauli, Mrigakunja, and Amaltari Buffer Zone User Committees (BZUC) as well as the Someshwor, Gardi Chure, Radha Krishna, and Baghmara Buffer Zone Community Forests (BZCF).

BARRIERS TO INCLUSION

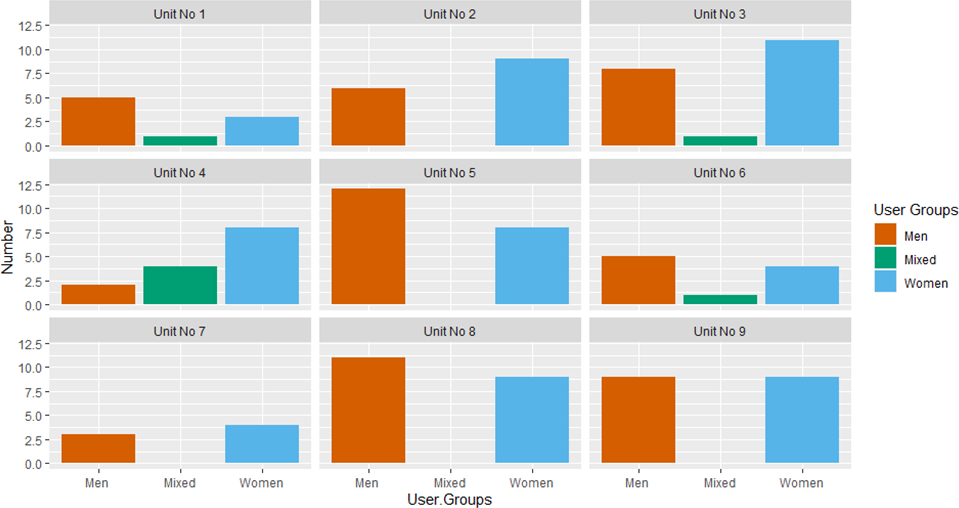

The survey found that women are underrepresented in all the BZUCs despite women user groups being larger. Nepal’s Buffer Zone laws dictate that each BZUC has 13 members. Each BZUC is made up of nine units, and as many representatives are elected from those units. The elected members have the authority to choose the remaining four members. This meant that indigenous peoples, marginalised groups, and women have a far lower chance of being elected.

Indeed, out of the total members, Paachpandav and Mrigakunja BCUZs had four women, Meghauli had three women, and Baghauda had only one woman, whereas Amaltari user committee had no woman member.

In contrast, the BZCF are relatively more inclusive of women, with two out of four surveyed BZCF comprising half women members. Additionally, some grassroots user committees are made up entirely of women.

Most women members of the user committees are not appointed through elections, but chosen by elected male members, and are not given positions of leadership.

“Women have been the ones protecting the forests ever since the concept of forest conservation initially emerged,” one female participant told us during a focus group discussion.

People would get angry when the women stopped them from cutting down trees and grass, and grazing cattle in the jungles, she recalled, adding, “We were dedicated to the user committees. However, we are no longer involved in the committees, nor are we invited to meetings.”

When asked about the absence of women in the user committees, one BZUC chairperson responded, “There are only men here because they won the election. Women are unwilling to run for the election. How will they fit into the committee if no woman has ever run for election?”

However, not only are women deprived of the chance to contest elections, the chances of them winning polls are also very low because a majority of the positions in the committee will already have been allocated by political parties to their male cadres.

Women from marginalised communities face further hurdles.

“No male member from the Musahar community has been elected in the user community, if they had, they could have suggested that women from our community be included in the committee as well,” said a female participant from the Musahar community.

While the native Musahar and Bote people lack representation in the BZUC, indigenous people did make up the majority of the members in the committees, while Dalit members were included in some collectives. However, only one committee is led by an indigenous person. The others are chaired by upper-caste hill migrants. In addition, no committee had any representative with disabilities.

One of the key reasons for the under-representation of marginalised communities in Nepal’s BZUC is its non-inclusive policy. When Nepal’s Constitution was promulgated in 2015, residents living in proximity to protected areas across Nepal had hoped that policies relating to buffer zones and their governance would be reformed to reflect Nepal’s new socio-political reality. But this has not been the case.

However, this has not discouraged indigenous Nepalis, who have continued to demand buffer zone policy reforms that ensure the inclusion of women, indigenous and marginalised communities.

In addition to policy revision, it is necessary to reform the buffer zone election so that it is more participatory for underserved communities. Reforms should also regulate the number of members in a user group.

Similarly, the budget allocated for buffer zones must be used on activities that benefit conservation instead of local infrastructure development. Women, people with disabilities, indigenous and marginalised communities should be the primary beneficiaries of budget dispensation. Crop damage compensation, which currently is Rs10,000, can be increased by five times to Rs50,000.

Policy revisions should ultimately guarantee the rights of indigenous communities like the Sonaha, Bote and Musahar to practice their culture and traditional livelihoods and receive a formal education. Buffer Zone User Committees must apply indigenous conservation practices for park management.

Birendra Mahato is an elected member of the Ratnanagar Municipality Ward 6 and Founder Chair of the Tharu Culture Museum Research Centre in Sauraha.