Doomscrolling democracy

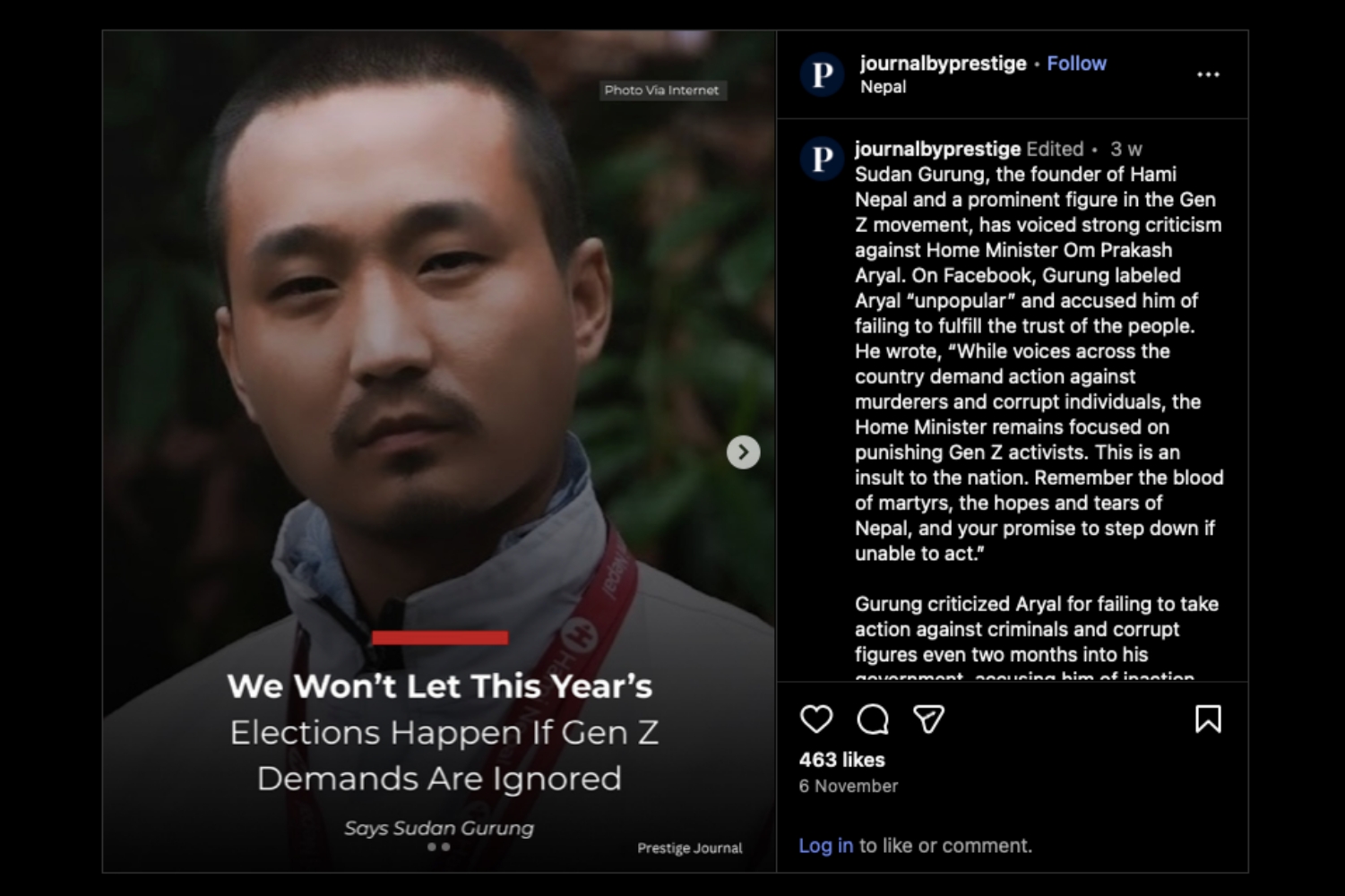

Rumour, bias and propaganda have always been a part of the informationsphere, but what makes it different today is the velocity at which falsehood spreadsThe post on Instagram has an image of Sudan Gurung. Over the top is the message: ‘We wont let this year’s election happen if Gen Z’s demands are Ignored’. The account’s bio is ‘Uniting Nepalese Through Independent Investigative Research.’

Post like these have become a template for the information ecosystem in the aftermath of the GenZ revolt in September. Social media feeds are saturated with content that uses multimodality of captions, video, audio, to convey alarm and warnings about how GenZ aspirations are being subverted.

Research by MIT showed that on X false news reaches 1,500 people six times faster than the truth. Fake news goes ‘farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth’, researchers concluded. Narratives compete on platforms, and users gravitate to the shock-value of the news and not to factual precision or nuance.

“On social media misinformation easily mutates into disinformation,” says media literacy trainer Deepak Adhikari. “The news we see on social media are often out of context, with little information that misinforms more than inform.”

Indeed, today’s ‘Post-Truth Society’ is characterised by a media environment where users give more credibility to their pre-existing beliefs and emotion rather than objective facts or subjective nuance. Post-Truth does not refer to what comes after the truth, but rather a cultural or information environment where pre-held personal beliefs shape public opinion, not facts.

Rumour, bias and propaganda have always been a part of the informationsphere, but what makes it different today is the velocity at which falsehood spreads. The news cycle is short, and before content can be verified the damage is already done.

Adhikari says that pre- and post-publication fact checking can be a potential antidote. However, when a video with misleading content goes viral, and even after fact-checkers catch up to correct it, the fear-mongering, anger or hate has already spread.

In Nepal’s social media, apparently everyone is tarred as guilty, or funded by a foreign government. Calls to dismantle federalism, restore the monarchy, or teach political leaders a lesson by supporting authoritarian alternatives are no longer fringe ideas discussed in private. They circulate routinely in the algorithmic streams legitimised not by evidence but sentiment.

When misinformation becomes the default, nostalgia for a mythical prosperous past begins to look like a rational response. While these positions are not new, their algorithmic amplification gives them perceived legitimacy that makes it hard to estimate, or far exceed, their actual political support.

“We have not highlighted the achievements of our multiparty democratic system, and the new generation has not experienced authoritarianism,” Adhikari explains. “Therefore statements like federalism is expensive and the monarchy was better have taken up space, because the evidence of the counter narrative is underreported.”

There is a positive side to social media. The GenZ movement took on momentum, and the protestors organised and supported each other through the very platforms that are now full of content that can potentially derail the democracy they wanted to strengthen. Just like it was trendy to be revolutionary during the protests, it is now trendy to be skeptical and to distrust the very people who were installed in the interim government through online voting.

Such is the architecture of social media: it rewards immediate reaction over reflection, and due to its interface design, it not only shows what could be relevant ‘for you’ but also tells you what others are thinking about that.

The role of the mainstream press as the traditional gatekeeper of information has been superseded by the digital sphere — both in access and sharing. This poses new challenges because social media content may not be news, and just because a page claims to be a news site that does not mean it is journalism.

Social media feeds are not chronological newspapers but an algorithmic marketplace. TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube all rely on recommender systems, now powered by AI to keep users on their platforms for as long as possible. The feeds then collapse the distinction between credible news, speculation, parody, and deliberate disinformation, especially in a politically volatile environment.

Everything appears in the same vertical stream, formatted with similar fonts, voiceovers, and music, making a platter of content that they know you are most likely to consume. For Nepali users, this has created personalised and parallel political realities. Two people living in the same household may open TikTok and encounter completely different idea of the problems and solutions of Nepal. One is fed content in favour of elections in March, while another pushes conspiracy theories about anti-GenZ activities aided and abetted by foreign powers.

None of these feeds reflect the whole picture. Each reflects what the algorithm has learnt will capture user attention. Academics have long found that social media sites do thousands of A B testing to silently optimise which colors, captions, or video formats users respond to most intensely.

Tests help design the most addictive feeds. Interface interference allows platforms to limit discoverability of certain features such as the ‘Logout’ and ‘Privacy’ settings so the system remembers users preference for the next time they are scrolling the platform.

When faced with such infocalypse, we have the option to withdraw and not engage with our feeds or our phones. But billions of dollars have been spent by Big Tech to keep us hooked. We need more structural revisions that integrate the need of a safer online environment. Media and digital literacy must be woven into both formal education and public institutions. It cannot be an optional topic or a workshop for a select few.

Students must learn how algorithms work, how misinformation spreads, and how to verify information before sharing it. Adults need community-level programs that help them navigate the online world that now shapes politics.

Content creators also must be held accountable. Profiles posing as news sites must also be brought under the same scrutiny as the mainstream press. Directives for social media journalism, a section in the Press Council’s Journalism Code of Conduct can be introduced as provisions that foster transparency and ethical journalism practices on social media. Creators should pledge to verify facts, cite sources, and clearly label opinion or commentary.

While this will not entirely curb disinformation, it can be the first step towards a digital public sphere that can host democratic dialogue with nuance and facts.

Says Adhikari: “Journalism doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and our knowledge space, academia, think tanks, research centres, archives, are scaffolding to support journalism, and we must make them stronger. The role of journalism can be to humanise the news and journalists can be storytellers, but the responsibility of the information ecosystem does not rely on journalists alone.”

Ayusha Chalise is a communication and development scholar specialising in how politics is experienced in the digital space.

writer