Our great stories

On International Migrants Day, a look back at some of the 75 Diaspora DiariesThe Diaspora Diaries series in Nepali Times over the past four years has profiled people on the move, so it is fitting that the theme for this year’s International Migrants Day on 18 December is My Great Story: Cultures and Development.

The past 75 episodes of Diaspora Diaries have featured inspiring stories of Nepalis -- their trials and tribulations, accomplishments and aspirations. The people and decisions they made, the talents they nurtured. The odds were stacked against them in Nepal, and moving offered a way out.

By sharing their stories, we became part of their journeys. And they, part of ours. The image marking 75 stories is symbolic: migrants holding the mic and sharing stories in their own words.

Stories have the power of influencing narratives, and this is particularly relevant in the migration discourse that is vulnerable to populism, misguided representations and myths. Stories help broaden the understanding of the migration experience: not as reductive binaries of good or bad, and of heroes or victims.

We caught up with some of the people profiled in Diaspora Diaries to see how they are doing. Had they finally decided to come home? Were their children now migrants? How is their business back in Nepal faring? Will they stay, or will they leave again?

We know Bipin Joshi through fragments of memory from his friends. Nepal waited for his safe return, but heard that as a hostage he did not survive Israel’s war on Gaza. Nischal Pandey, one of the Nepali students who survived the 7 October 2023 Hamas attack is now working on his Master’s in Nepal.

Also in Israel, Prabha Ghimire worked as a caregiver, and returned to Nepal after 19 years when her 101-year-old employer died.

We call migration to the GCC and Malaysia ‘temporary’, but many of those profiled are still there after decades. Homnath Giri was featured in the very second Diaspora Diaries in 2022, and has been working in Kuwait for 21 years in companies where as managing he prioritises the recruitment of Nepalis.

When we called up Ishwar Chaulagain who has country-hopped Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and Seychelles, and half-jokingly asked him: “Which country are you in now?” He was in Kuwait, his house in Nepal is now built, and he has earned a dual diploma online.

Bhim Bishwakarma the caregiver-cum-artist has been in Bahrain for 18 years, and was back in Morang recently to get married. Coffee aficionado Laxmi Timilsina got promoted to assistant manager in Qatar, and said that his life feels complete after bringing his family to Doha and being blessed with a baby girl. UAE-based artist Jeevit Khadka is preparing to publish his collection of poetry धागो (Thread).

But how un-returnable has this country been made that people stay on for decades? Migrants tell us that there is always a reason to postpone returning.

There is also an increasing trend among Nepalis abroad to start their own side businesses or use where they are as a launch pad for onward migration. Singer Ashik Shrestha started his own lounge with friends in the UAE where he performs. Aliza Basnet who was working in the UAE when we interviewed her has now taken her bakery skills to the UK.

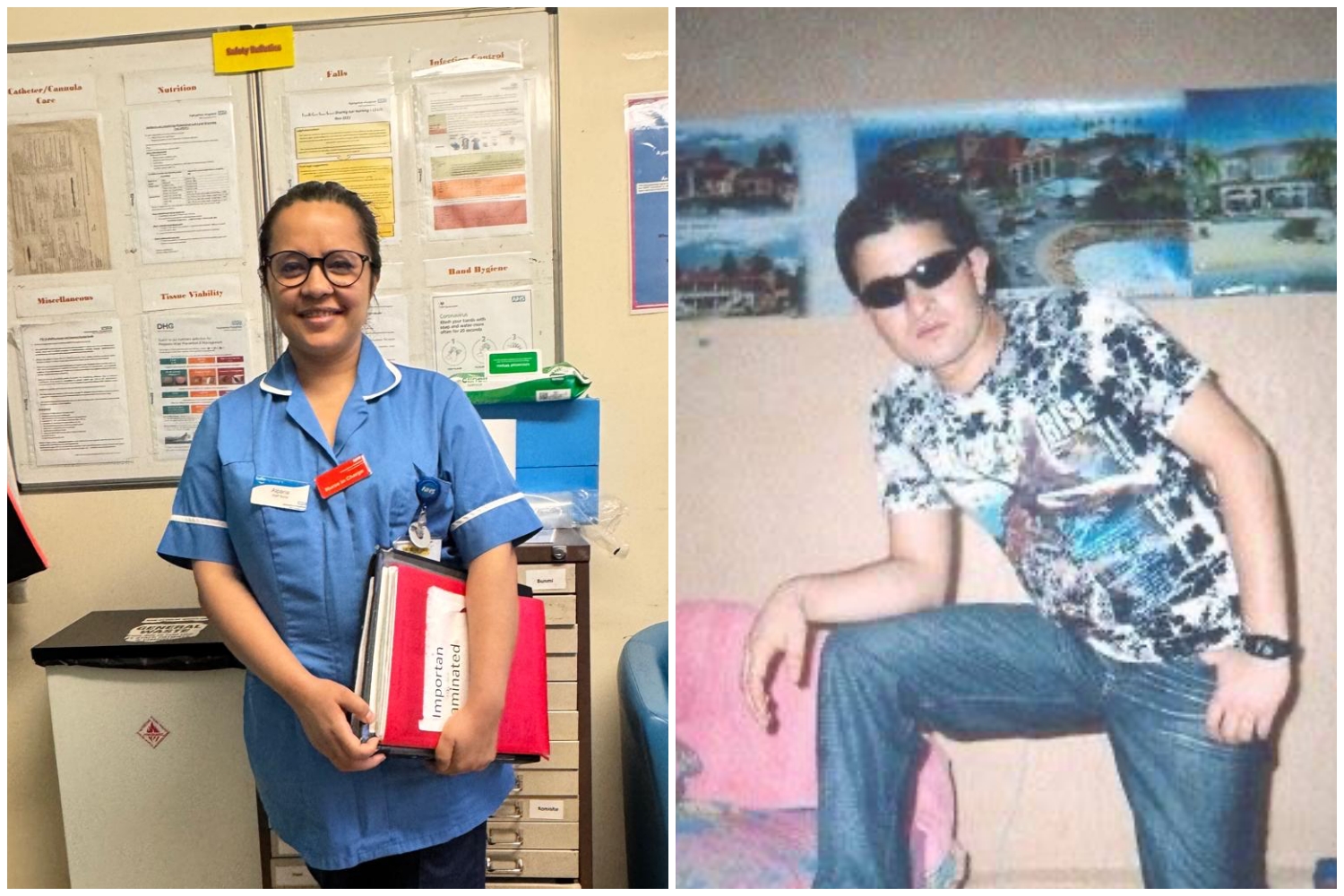

Trailblazers continue to trail blaze. Shanti Bhandari who drives a double-decker tourism bus in the UAE has now obtained a truck license, always an interest to her. Turkey-based Shyam Kala Rai has not yet opened her Nepali restaurant given the economic climate. Since sharing her story in 2021 about her sacrifices for her children, her daughter has graduated as a nurse in Australia, and her son now works as a chef at QuickChina in Turkey.

Anil Shrestha was in Malta with his brother Ajay who died in a bike accident in 2022. Anil recently got married and has returned to Nepal, and is questioning the decision given poor employment prospects. The family still mourns Ajay’s death and has not yet received accident compensation.

Sajita Lama, who was abused as a domestic worker in Lebanon, has still not recovered her unpaid wages of 10 years of work.

The importance of compensation after mishaps in foreign employment is evident in Antare Khatri’s case. He continues to receive benefits from Malaysia’s Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) after losing his hand in a workplace accident. Recently, one of his sons went to Malaysia and the other to what he refers as “ठुलो देश”, Greece.

UAE returnee Dalbir Singh Baraili has also passed the migration baton to his children who are now in the UK. While survival is manageable with earnings in Nepal, he says covering weddings, large expenses for festivals and illnesses puts a strain on finances.

Rudra Sapkota sold his vegetable shop in Nepal and is enjoying a retired life, watching cricket, going on morning walks. “It’s not that bad,” he reckons. After spending 30 years in Saudi Arabia, his sons are now in Canada and Dubai.

Narratives like how remittances are not used productively are often part of public discourse in Nepal. But what is the measure of productive investment?

Without remittances, some families struggled to even eat or send children to a decent school. Migrants have used savings to retire parents to a concrete house, or save enough to pay for medical costs to save the lives of close relatives.

Migration needs to be viewed through a wider lens — a continuum that stretches across generations. The rewards of today’s investment may come much later in better human capital, health and migration outcomes of the descendants of migrant workers who can afford to go to university.

UPS AND DOWNS

Some Diaspora Diaries stories are on returnee entrepreneurs, and the common sentiment is that Nepal’s economy is not conducive to business.

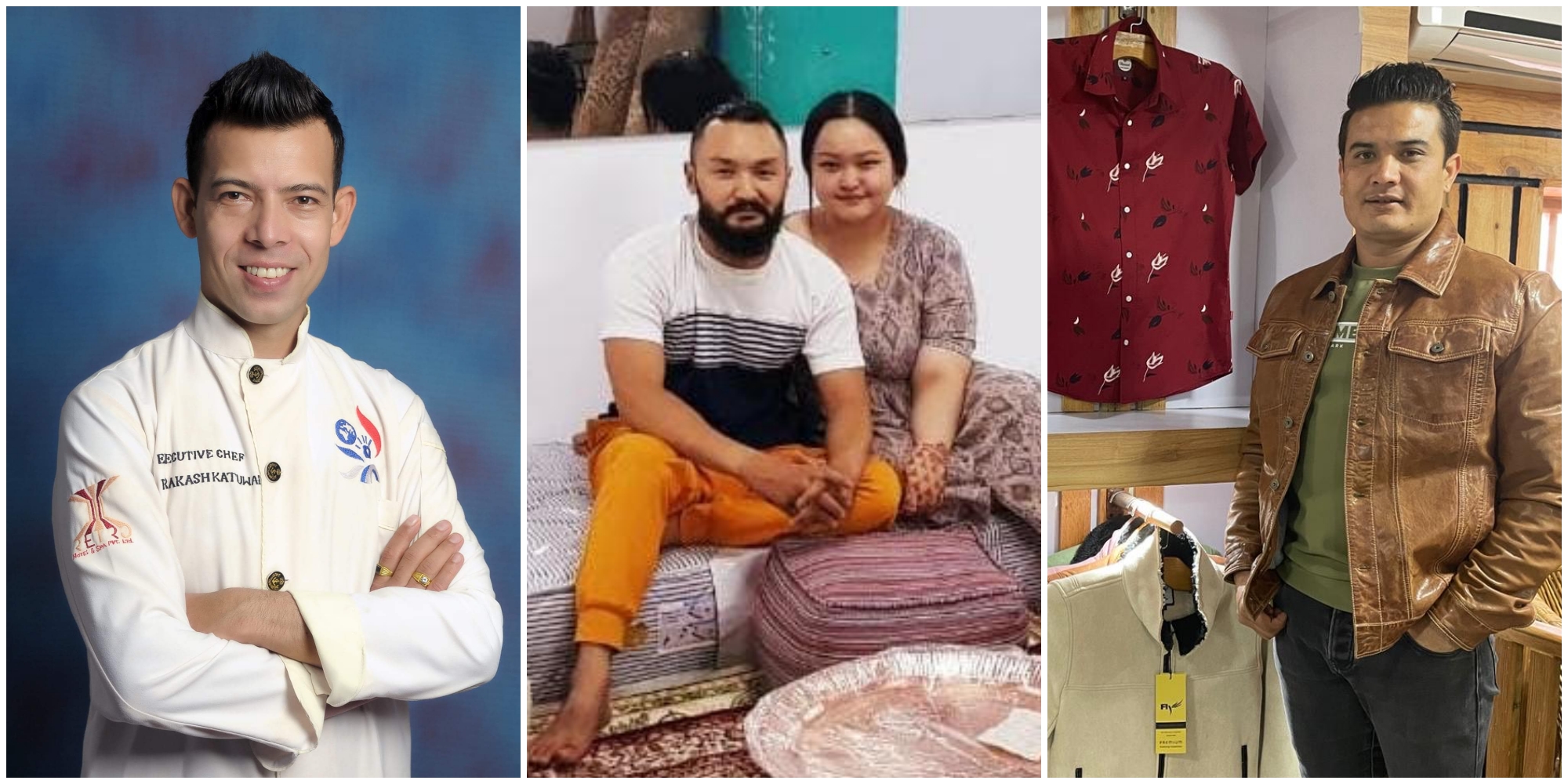

Prakash Katuwal’s Turkish restaurant in Kathmandu is doing well, he is now a celebrity chef of sorts with wide engagement on social media, and he also is part of a cooking show. “I am still a simple man and do dishes till 1AM every night,” he says.

Factory owner Krishna Timilsina has expanded to start the clothing store Looga Ghar, while expanding presence internationally through exports and registering a tailoring and boutique branch in Japan.

Chiyaspot owner Gautam Guvaju has also started a new Chiyaspot branch, and has come out of his shell on social media where he shares his journey and inspires youth.

The trio Korean returnees Shahadev Gurung, Prabin Shrestha and Dil Bahadur Tamang have expanded their meat shop including a new branch, and a small Korean restaurant. The nine returnees who set up Chef Burger team have opened their eighth burger outlet in Tinchuli.

Prabin Shrestha recently completed meat processing training in Korea, and his supplier and another returnee Sushil Lama received funds from the Nepal government to expand and upgrade their pig farm.

Sunil Bhujel came back from Qatar and UAE to expand his maintenance business to road construction. Qatar, Dubai and Seychelles returnee Shiva Sharan Khatri has added a resort in Chandragiri in addition to his facilities management business.

Business fluctuates, rent does not. This can spell trouble especially for small businesses. Babare Bomjon, who runs Akbare Momo, says shrinking demand has made him rethink his venture. He is looking to pivot to his own property-based business model because rent is unmanageable particularly when business goes up and down.

Burger Shack owner Rohit Shrestha is also facing upheavals, but has added bakery products, including bagels. After returning to Nepal from Qatar and Saudi Arabia, poet Mahendra Thulung Rai also feels the pressure of rent for his venture, Purbeli restaurant. He is still writing poetry, but considers re-migrating because of the cost of living and doing business in Nepal.

Three years ago, when we spoke to Tilu Sharma, who has been in Qatar for 21 years, there was a debate about allowing overseas Nepalis to vote in the 2022 elections. He repeated what he told us three years ago: “Our notes work, our votes don’t”.

With elections due in March 2026, whether out-of-country voting is allowed or not, narratives around migration will matter even more than before. Candidates will use campaign slogans like “बिदेशको पसिना” and “बाध्यता” to portray migration as a result of state failure.

With few exceptions, stories shared by migrants largely show the absence of practical initiatives to help them in their journeys. Nepalis are leaving silently, returning silently.

A recently released government report showed that the number of migrant workers returning via Kathmandu airport crossed half a million each year in the past two years. Why have they returned? What factors would make them remain and use their skills here?

Temporary migration should be alleviating concerns of both the migrant origin country like Nepal that can mobilise returnees who have added financial and social capital, and that of the host countries that fight with their own increasing anti-immigrant sentiments despite migrant contributions in unfilled vacancies.

The Diaspora Diaries network has also helped to improve migration. Rohit, Shiva and Tilak, for example, have provided guest lectures to young Nepalis headed out in entry level positions in the hospitality sector — just as they had decades ago.

When abroad, the three have been responsible for interviews and promotions on behalf of their employers. Discussing practical and enabling factors for successful careers and post-return plans while talking about struggles ahead was helpful.

Why does this matter? Because we want outgoing candidates to reimagine migration and see how they can maximise its gains. No matter whether they were pushed or pulled (or both) no matter their backgrounds and the opportunities they have had access to growing up, by the time they get on the plane in Kathmandu, how do they make the most of this experience?

Each Diaspora Diaries story ends abruptly, but the lives of those profiled carries on. Will the UK provide better special education services for Alpana’s son? How will Babare Bomjon come out of the slump in his momo business? What is next for Prabha in Nepal after 19 years away? When will Sajita and Ashish finally get their owed dues.

We continue to search for contact details of the anonymous returnee from Malaysia and Qatar from the very first Diaspora Diary in January 2022 – the migrant worker who inspired us to write this series.

Upasana Khadka heads Migration Lab, a social enterprise aimed at making migration outcomes better for workers and their families. Labour Mobility is a regular column in Nepali Times. The past 75 episodes of Diaspora Diaries series can be accessed through site search, or by clicking the hyperlinks above.

writer