Who gets to recruit for Malaysia?

Malaysia’s 10-point recruiter selection criteria risks punishing the good migration actorsImagine a high-end fair trade tea brand from Nepal that has done everything right, with ethical sourcing practices and international certifications. It has built a loyal base of socially conscious, premium customers in an export market and focuses on quality over quantity.

Then one day, a government in the export market introduces a new ‘listing criteria’ that requires exporting a certain amount of tea to at least three countries in the past five years. But this was never a numbers game, it was about a niche market of socially responsible tea lovers.

Suddenly, fair trade tea companies are restricted from exporting tea to that country.

Pretty unfair for the company, for consumers, for the tea sector. More importantly, for tea farmers and families benefiting from fair standards.

The overseas labour industry is facing a similar risk as recruiters, including those that have adopted ethical standards, may soon be barred from finding workers for Malaysia.

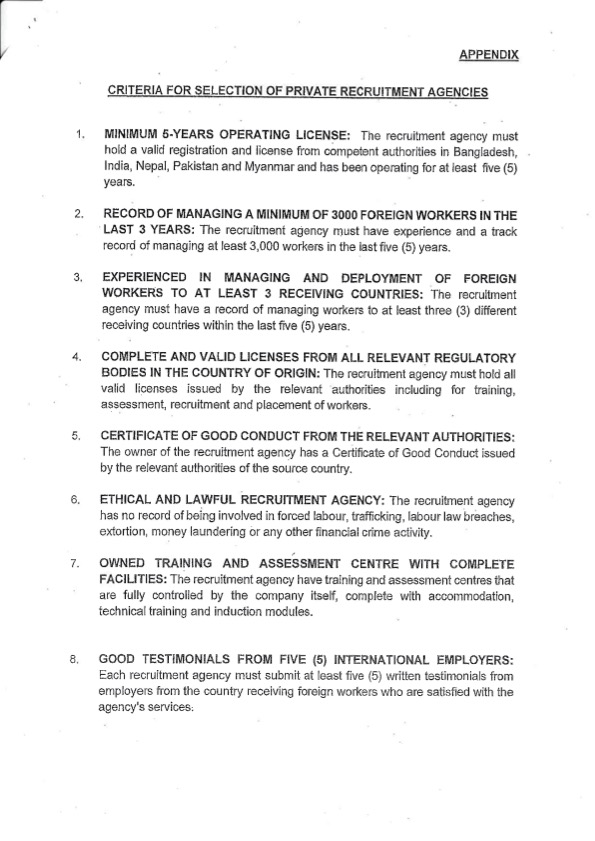

On 27 October, the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent letters to five countries including Nepal, Bangladesh, Burma, Pakistan and India to ‘rationalise the number of licensed private recruitment agencies permitted to facilitate recruitment and placement of workers to Malaysia’.

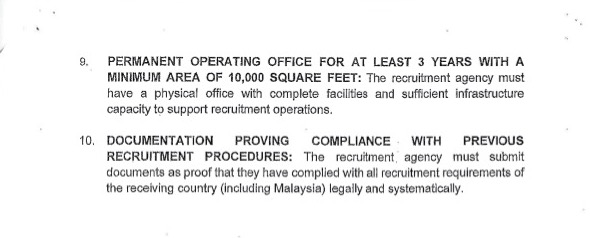

The letter includes 10 criteria for private recruiting agencies including at least five years of operating experience, deployment of 3,000 workers in the past three years of operation, experience sending workers to at least three countries, a 10,000 sq m office maintained for three years, valid licenses and good conduct certificates, five employer testimonials, and operating their own training and accommodation centres.

Two conditions stand out as potentially harmful to Nepal’s ethical recruitment movement. First, although the letter cites a minimum of 3,000 workers, it says three years in the heading and five in the body text. A big enough difference to affect a significant number of recruiters from making the cut, but problematic regardless.

Second, the requirement to send workers to at least three countries disproportionately impacts responsible recruiters in Nepal and elsewhere.

Turning the selection of workers into a numbers game is dehumanising. Responsible recruiters deprioritise volume, focus on quality of jobs even when business sustainability comes under threat as ethical opportunities that do not require workers to pay any feed and ensure greater transparency are difficult to come by.

Sending workers is further impacted by a series of external shocks. For example, in the Malaysian context Nepal banned emigration to Malaysia for two years followed by the Covid pandemic, and then Malaysia’s decision to stop the intake of foreign workers for the last two years.

Many ethical recruiters have focused on Malaysia because it is a more common labour market for responsible recruitment than other destinations like the Gulf. There is no credible justification to why responsible recruiters well regarded by scores of Malaysia-based multinational companies and with decades of experience should be ‘disqualified’ for not diversifying.

Finding jobs for Nepalis in new markets is difficult given fierce competition, challenges identifying companies which follow the employer-pays principle, lack of networks and shortcomings in marketing strategies. These factors hit responsible recruiters harder because profit-motivated employers are often unwilling to cover the costs and fees associated with workers’ recruitment.

“The volume of deployment does not determine a recruiter’s capability or the quality of services provided,” says Sujit Shrestha of the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies (NAFEA). Nepal recently scrapped the licensing renewal requirement that mandated sending at least 100 workers a year as it was impractical. The new Malaysian criteria is similar in nature, he added.

The ball is now in Nepal’s court at a time when the interim government does not even have designated heads in the Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Labour, Employment Employment and Social Security. When rumours about the Malaysian action started circulating, NAFEA had raised the issue, but was assured that this was not an attempt to set up a syndicate.

How will governments and recruiters in other origin countries now respond? There is precedence from Bangladesh. Dhaka-based journalist at the Daily Star, Porimol Palma who says, “Earlier, the Malaysian authorities had selected 101 Bangladeshi recruiters unilaterally, despite Bangladesh’s call for a syndicate-free recruitment mechanism.”

Between 2022-2024, 450,000 Bangladeshis were recruited under this system with workers paying between $4,500 and $6,000, even though the legal limit was $750. Palma attributes part of the high fees workers had to pay were for commissions or bribes to recruitment syndicates.

Adrian Pereira heads the North South Initiative in Malaysia says: “The criteria seems a bit fishy, as they do not appear to address the actual problems in the the recruitment of foreign workers. Some of the criteria seem to encourage a system of monopoly or syndicate rather than a rights-based approach. Every government has the right to set criteria for recruiters, but conventions and ILO (International Labour Organization) standards on recruitment exist. It looks like we’re back to square one.”

Whether migrant origin countries including Bangladesh and Nepal accept the terms sent without reservations or push back in good faith remains to be seen. In an ideal world, a collective stance should put workers’ needs and welfare at the centre. How rational is the proposed ‘rationalising strategy’? What aspects of it are promising to curb recruitment abuse and what merits serious reconsideration?

Even if the move from the Malaysian side is well-intentioned to address rampant malpractices migrant workers face, Nepal should deliberate on the conditions set, the collateral damage especially on the responsible actors and small but capable recruiters. Alternate options that might serve everyone better before rushing to respond with a chosen list by 15 November. If the proposal is accepted, how would it be done in a transparent and accountable way?

It is noteworthy that Indonesia was not listed even though it has the most workers in Malaysia among the 16 countries that send migrants to Malaysia.

The Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), the ILO, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and certification programs like On the Level (OTL) also need to use their leverage to ensure that recruiters, including those they have trained or certified on ethical recruitment principles, are not penalised.

This is more than just about protecting the ethical recruitment movement, but raising even more basic questions: Who can legally be a recruiter in Nepal? There are already obligations like hefty security deposit and minimum office requirements. But requirements to have building facilities with ‘accommodations’ or ‘testing centres’ are not among them.

There are 1,150 plus players in Nepal’s recruitment sector, with a few hundred engaged in the Malaysian market. A unilateral selection criteria could risk foul play, or lead to unintended, unfavourable consequences.

To be sure, overseas recruitment in Nepal is known for ‘settings’, corruption, dog-eat-dog competition, and collusion. The profiteering is out of control, often at the expense of workers. But the solution does not lie in stifling the industry with criteria like deployment volume, building worker accommodations or expanding office floors.

The focus should instead be on enforcing rules and laws in both countries that govern the industry, and the Malaysian labour agreement that has not been renewed since October 2023.

Meddling in the industry in ways that harms fair competition and ethical actors means workers suffer. The only issue that should be taking precedence is: how will Malaysia’s 10-point criteria and planned arrangement affect migrant workers?

We have seen how for identical Malaysia-based jobs, one worker might pay zero while another pays up to Rs400,000, depending on the employer and recruiter. It is unclear if the 10-point selection criteria rewards the responsible employers and recruiters.

As a longstanding host country for Nepali migrants, Malaysia deserves credit for nurturing the small but growing ethical recruitment industry here. Export-oriented companies in Malaysia need responsible recruitment partners and have mentored recruiters to strengthen their practices and move away from worker-paid models.

The business case for ethical recruitment standards has led many recruiters in Nepal to pivot with many now in various stages of transition from traditional to hybrid or purely ethical practices. This progress needs to be acknowledged and built upon.

Large, well-networked recruiters with large physical assets and high volume of workers seem to be the winners of Malaysia’s 10-point criteria after two years of waiting for the Malaysian market to reopen.

Responsible recruiters endure long periods of minimal or no deployments that threatens their survival. The letter now sitting on the desk of the interim government in Nepal deepens the concern: rather than just failing to recognise or reward responsible recruiters, does the international recruitment market actually punish them?

Upasana Khadka heads Migration Lab, a social enterprise aimed at making migration outcomes better for workers and their families. Labour Mobility is a regular column in Nepali Times.

writer