Usha Sherchan: Humming a tune of her own

When Usha Sherchan talks about Pokhara, where she grew up, she gets a faraway look in her eyes. Everywhere around us were open fields, but the street we lived on was a place for traders, she says. Tangbetans from Jomsom would come down to our area for six months during the winter. They sold homemade alcohol, jimbu, and ayurvedic plants that you can only get in the mountains. I was always in love with their donkeys; they were decorated with all sorts of bells and colourfully embroidered materials. Pokhara’s nights were black like molasses, but we played hide-and-seek in this dark. It is funny now, but on a moonlit night I used to think that the moon was always following me, I could never hide from it –– so I would take it with me wherever I went.

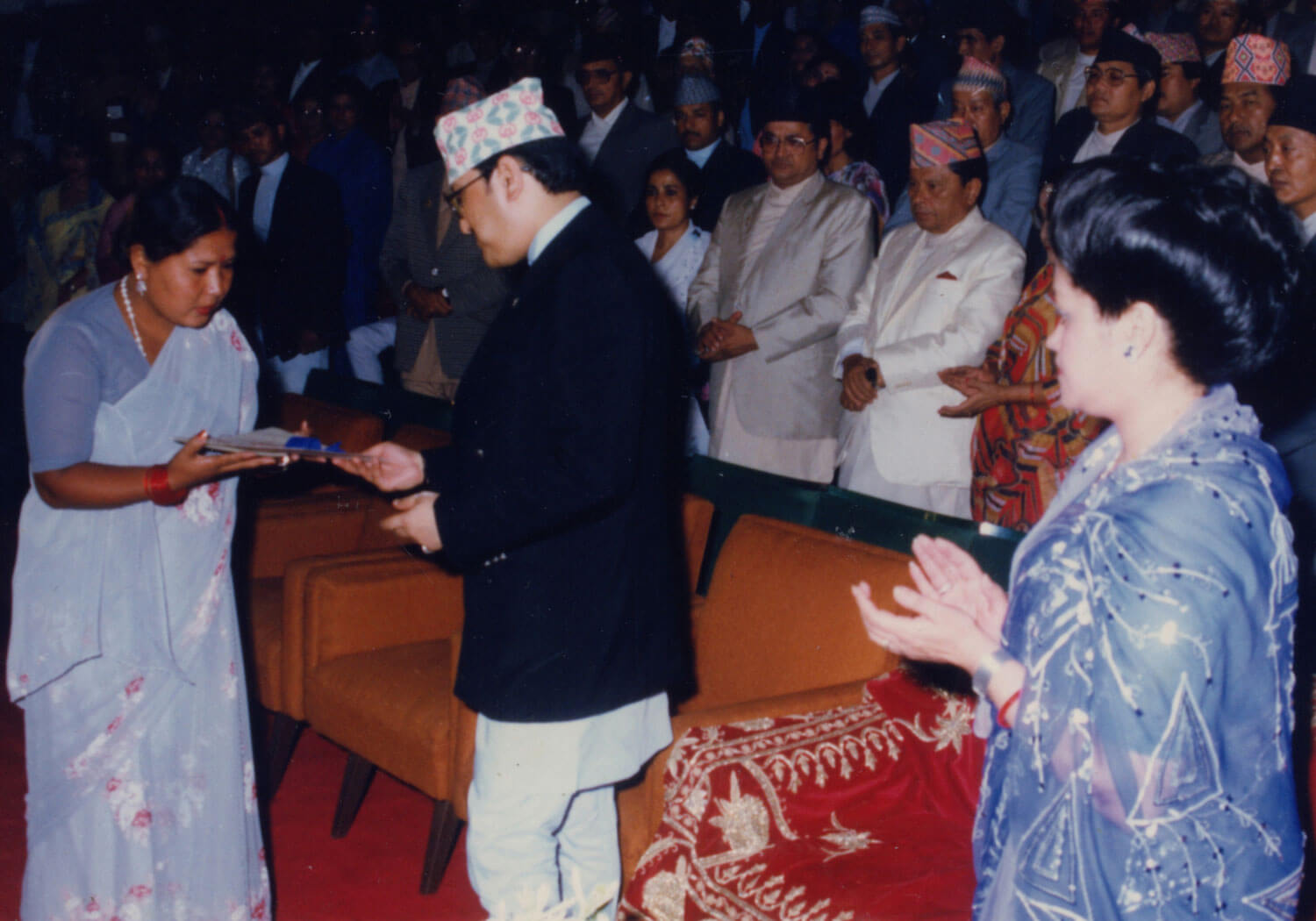

Born on 22 August 1955 in Nalamukh in Pokhara, Usha Sherchan is a beloved figure on the Nepali literary scene. She has published three collections of poetry: Najanmeka Asthaharu (Unborn Beliefs, 1991), Aksharharuka Shiwirbata (From the Barracks of Words, 1999), Sarwakaleen Pinda Ra Jagritika Shankhaghosh (Pain of All Ages and the Sounding Bell of Awakening, 2006). Usha has also written a collection of short stories, Tesro Rang (Third Colour, 2013), and a novel, Aadhi (Agony) which was released earlier this summer. Usha is also a lyricist who has written many popular songs. For her contribution to literature and music, she has received over 13 awards, including the Parijat Rastriya Pratibha Puraskar and the Ratnashree Suwarna Padak.

Read also: Toya Gurung: Nepali literature’s Thulnani, Muna Gurung

When I ask Usha what her favourite poem is, she tells me it is Ma, Cleopatra. Shristiko Euta Sundar Bhool (I, Cleopatra. Creation’s Beautiful Mistake), a poem she wrote when she was still Usha Bhattachan, a 20-some-year-old single woman from Pokhara. Cleopatra, to me, was a symbol of the world’s most beautiful, youthful and powerful woman. Yet no matter how desirable women are, we are always mistreated, our bodies always hated. I wrote this poem to understand the cost of being a woman in my community. All women have to bear that cost no matter how beautiful, young, powerful or desirable they may be, she says.

Usha also writes about women’s desires and sexualities. Her stories and poems are about the bodies of women that make all sorts of journeys -- physical, mental and emotional. Usha is also one of the few writers who writes queer stories with LGBTQ characters. These stories are usually open-ended, leaving room for both danger and hope. In this month’s Lightroom Conversation, Usha and I talk about the importance of telling stories that may not always be our own; creating alternate realities through fiction, the punch of a poem that is a muktak, and the process of writing.

Usha Sherchan: In Ganesh Tol, Pokhara, where I grew up, every evening the men used to sit on dabbalis and play tablas, sing songs and smoke weed. The women never had that kind of space. The only time we were free to do whatever we liked was in the gufa room of a menstruating Newar girl. As you might already know, before or after a Newar girl’s first menstruation she is kept in a dark room for 12 days. No men are allowed to enter that space, but her friends can come. So we would gather in that dark room and eat all sorts of food, sing, play and dance. That was when we could really let go.

Read also: Pancha Kumari Pariyar: Still She Rises, Muna Gurung

Muna Gurung: Yet that seems occasional. What were some everyday spaces available to women in your community?

U: Swamiji’s sermons. He was mesmerising: he told his stories with flair and a lot of arm and body movements. His audience was all women. They appeared with Puja paraphernalia and sat with shawls wrapped around them, listening to these stories of different gods and goddesses. But these women were older – they were the sasu generation. The buharis and other younger women were busy with endless house chores and working the fields. But once a week or so, my sister and I would take all our clothes to the river and spend our day washing them, drying them on large rocks and trees, taking naps. On good days, our brothers would deliver food for us, otherwise we would bring our own food and have a large picnic. We were all women -- and I guess that was an everyday space we could claim.

M: These women were Newars mostly?

U: Newars, Brahmins and Chhetris. We were the only Thakali family in that area. But as a result of that, I think, we began to lose our culture, we became more Hindu.

M: Say more.

U: For instance, Thakali women were never considered ‘impure’ during menstruation. We could go into temples, kitchens, wherever. But after living closely with others in the community, we also began to take on their customs of not letting menstruating women into kitchens, temples. Also, my parents used to be able to speak in Thakali, but they were ashamed of being called bhotey, so they stopped speaking in their language. (Pauses). Thakalis have always been a matriarchal society: women married several men, women who were widowed were encouraged to remarry, and women who had married twice or three times were not seen as spoiled goods. It was very common for women of my mother’s generation to have been in several marriages. But all that changed -- now our society is patriarchal. My father began to have that kind of thinking, which got passed down to my brothers. Even my husband falls in the same category. By coming down from Thakhola and settling in Pokhara, we got rid of all the progressive good things and picked up all the negative practices that still continue today.

M: Is this why you write so much against the patriarchy?

U: (Laughs). I write about people and places. I write about my experiences, what I have seen, felt, heard, read about, and patriarchy is not something I have been able to escape. Have you? I guess I have also always been a sensitive person, so I feel the need to write about all the things that affect me.

Read also: Maya Thakuri: Writing between the lines, Muna Gurung

M: How did writing start in your life?

U: So during a gufa, we would sing songs and I would make up new verses on the spot. I also grew up around a lot of my family members who were artists: my grandfather, Abuwa, was versed in poetry, songs, plays and was even a good cook. He ran a clothing/tailoring store with my father. He was the one who taught me how to write. He would spread red sand on a slab of stone and using his finger, he would teach me to outline the different shapes of the alphabet. Later, he brought slate for me and then he would chisel young bamboo stems into pens with sharp tips. I think the ability to tell stories came from my mother: she was not educated, yet she was the clearest orator and storyteller. The stories she told were religious but I loved listening to them because they felt like I was watching a series of moving images.

M: When asked how to become a successful writer, the famous author, Zadie Smith, once said that one has to read books as a child to be a good writer. I always found that flawed. I grew up with no books in my house -- can I never be a writer, then? But ‘books’ look different in different cultures.

U: As a child, I did not have access to books, but then in 7th grade my friends Indira Bataju and Sarita Duwa brought me all sorts of Nepali novels to read. I do not know where they got them from... There was a British library behind our house, but girls did not go there. My brothers would bring home books, and when they were not reading I would read them. Later, Sarita didi from Dhaulagiri Stores gave me some Hindi novels. By 9th grade, I had tasted all the literature available to me. Perhaps, this was the beginning of my training as a writer. Later, even when my parents urged me to get married after passing SLC, I came to Kathmandu with the help of the royal family. My father used to be the in-charge at the Hima Griha palace in Pokhara, and the royal family was kind enough to send me to college. I attended Ratna Rajya Laxmi Campus, where I became friends with writer Pratisara Sayami.

She and I used to write in our notebooks but we never showed it to anyone (Laughs). I believe in destiny. I think I was born to be a writer and therefore all sorts of surprises came from unexpected people in different places and phases of my life. My own hard work and resilience play a role in all this, of course, but there are certain things that are out of our control.

M: But your journey as a writer started in Pokhara and not Kathmandu, yes?

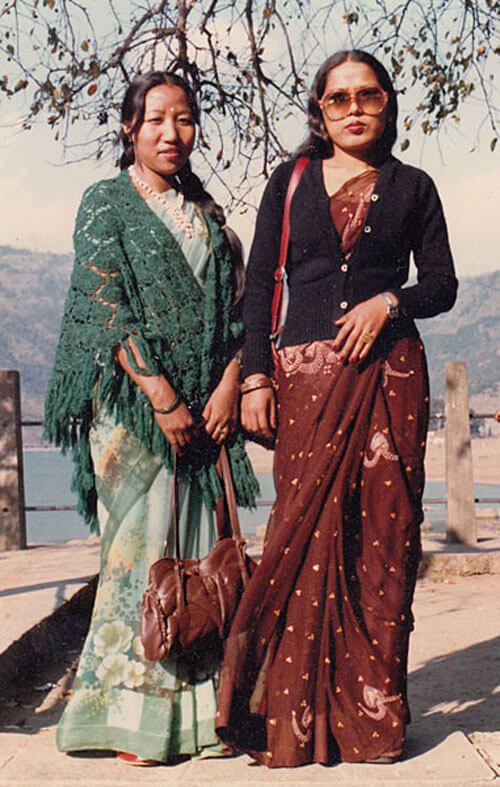

U: Yes. I went to Prithvi Campus in Pokhara for my bachelors, and I did not know it then but it was the stomping ground for many of today’s big writers and poets. Saru Bhakta, who was just Bhakta Shrestha then, was there, and so were Tirtha Shrestha, Prakat Prageni Shiva, Bikram Gurung, Arun Thapa, Binod Gauchan… the list goes on. Binod was a far cousin and I remember telling him that I wanted to meet Bhakta -- there was a buzz in town about him being a writer. But as a woman, you had to think 100 times before stepping into a restaurant or walking around with men, so I was scared to approach Bhakta on my own. These guys hung out at a tea shop just outside the campus. One afternoon, Binod introduced me to Bhakta at the tea shop: he was a scrawny man wearing a sad face, with long hair. One hundred and one percent like a stereotypical writer! (laughs). He probably saw me as a modern woman. Besides the weight gain, I used to be just as I am now: completely fashion conscious, and I had to wear sunglasses everywhere. My sari was always neatly wrapped around me, and I always made sure to look good. He took one look at me and looked away, did not talk much. But after that first meeting, I saw them often. One day, Binod flipped through my notebook and saw a poem he liked and copied it down. Unbeknownst to me, he sent it to the daily Gorkhapatra, where it was published. This was in 1978, it was a big deal to appear in the Gorkhapatra. Suddenly I became a writer overnight and now people, including my parents, knew that I wrote.

M: Did they try to stop you?

U: Yes, my mother would tell me that I should be getting myself ready to marry instead of wasting time writing poems. She was not happy with my choices, but I had a strange and powerful sense of self-confidence. I remember one year, we decided to charge people for literature. I knew that I was not doing anything wrong. Yes, I was meeting up with men but what did we do when we met up? We wrote poems together, we shared our poems with each other, we gave each other feedback. There were other women who wrote too, like Sulochana Shrestha and Hari Devi Koirala, but they either didn’t come out much or they started going towards other forms of art, like folk songs. But the few of us who met regularly, we slowly solidified into a group, then an organisation and a way of being. We started Pokhreli Yuwa Sanskriti Pariwar directed by Durga Baral. We held literary events but we did not know what we were doing. I remember one year we decided to charge people for literature. We were planning a muktak recitation event and issued Rs2 tickets. We knew that people would not be happy about it, but our philosophy was that poetry should come at a price, that it has value and that people should want to pay for it. And guess what?

M: Full house?

U: Absolutely. (Smiles) So, people were hungry for literature. We had female poets from Palpa and it was electrifying because most of them read their poems without looking at a sheet of paper. They were performing it. For poetry to be good and to land right, it has to be performed. When words become public on stage, it becomes a whole different creature.

Read also: Anita Tuladhar: The Gardener of Small Stories, Muna Gurung

M: Can you tell us a little about muktak?

U: It is a poem of four lines where the first, second and fourth lines need to rhyme but the third line is free. But also, the first, second and third lines need to be speaking to one another, but the fourth line can be different.

M: Are they supposed to be recited more than read on the page?

U: Yes, and they need to pack a punch. The definition of a muktak used to be loose – like the small poems that Sulochana Manandhar writes could also pass as muktak before, but now the rules are stricter, and we must adhere to a specific form. You will understand when I recite one... but I don’t like the ones I have in that book. (Pauses and scrolls through her phone. Looks up.) Ghaughauko anubhuti bhayeko cha jiwan / Pindaipindako anubhuti bhayeko cha jiwan / Nun tel chamal ma laam lagda lagdai / Anubhutiharu bich katai harai raheko cha jiwan

(An experience of one wound after another, that is what life has become / An experience of one pain after another, that is what life has become / As we stand in one endless line for daily salt, rice and oil / Lost in between experiences, that is what life has become.) The first line of the muktak is when you are raising a topic, like picking up a bow. Then the second line is when you select an arrow. In the third line, you aim at your mark, and in the fourth, you hit the target.

M: What a great metaphor to explain the structure of muktak.

U: I am currently working on a book of 365 muktaks. But I don’t know if I have that many in me. Because a muktak comes to me like lightning. When it comes, I have to scribble it down right away.

M: Last week, I heard Bengali poet Joy Goswami describe his process of writing a poem using the metaphor of a chase. He said the idea arrives at the dining table while he’s eating, and so he gets up and chases to write it down, but by the time he sits down at his desk the idea has escaped him. What is left is something completely different than what it was before. It has changed shape.

U: Exactly. The muktak comes to me just like that. But with songs, it is different. I find myself humming a tune and it will not be anyone else’s tune but my own.

It rises from within. And I hum it for a day or two, and then slowly the words start coming. Sometimes, I get so excited I type the song out on Facebook and share it. With stories, it is the characters that nudge me to write about them, they haunt me. Yet, with short stories, if you do not write it out at a specific time or you take a long break from it, it will go away from you. I do not know if it was my own laziness, or the fact that I was writing my stories in one notebook and my husband misplaced it, but I lost three stories. I could not get myself to rewrite them.

M: As though some magic left.

U: Exactly. I cannot explain it. When I wrote Aadhi though, I realised that with novels you should brace yourself for anything unexpected to happen. Characters and experiences that are buried deep in our subconscious resurface and enter the story. And there is nothing the writer can do but take them along with her into the book.

M: What is your research process like?

U: I read a lot of newspapers and I watch talk shows where interesting people are interviewed. I also meet a lot of different kinds of people, who in one way or another become the characters in my stories.

M: In Tesro Rang, you write about a kamalari girl, a gay son, a lesbian wife, a sex worker... do you get accused of writing stories that are ‘not yours’, so to speak? What I mean is, there is a lot of talk, at least in the literature of the English-speaking world, about who is allowed to tell whose story.

U: I do not know if that exists in the Nepali writing scene. If it does, I have not been accused of it. But one of the writers who reviewed Aadhi did say, amongst other things, how I should have written it from the point of view of a Thakali woman. I mean, the violence that happens to the main character of my novel doesn’t happen to women in the Thakali community.

M: But do you not think that literature is not merely about reporting what happens in society, but also about being able to put forth an imagination for the kinds of worlds we hope to live in…?

U: That is true. In that sense, I make sure that all the women in my stories win. For instance, there is a character in one of my short stories who can’t have a child and she is blamed for it, but childlessness is not only a woman’s problem. So she gets impregnated by her husband’s friend. Her husband loves the child at first, but when he finds out it is not his, he shuns both the wife and the child. Instead of the woman folding in, she thinks of herself as the fullest person because she has a child, and so she leaves him.

M: I think literature is also about creating alternative realities – be it fiction or nonfiction. You are also one of the few Nepali writers who has written queer stories or stories with LGBTQ characters.

U: I think it is important to tell these stories whether we belong to that group or not. Also, homosexuality or transsexuality are not new concepts. Look at Shikhandi from the Mahabharat -- he was a warrior but born a girl. We are all god’s creation, there is nothing wrong with us. My LGBTQ characters do not have a ‘choice’. Imagine some poor boy growing up confused, wondering why it is that he feels like a girl. They are naturally born that way so it is we, as a society, that must learn to accept them. But I know this is still not something we can digest easily. I do not need to go that far -- in my own family it’s hard to make my own husband fully understand about these matters. But as a writer, I have to be different. I must be open.

M: Is there a cost to being open, I wonder, especially as a woman who writes?

U: The costs are high. Let us just say that I have been very lucky to never have to worry about money or space when it comes to nurturing my writing life. I know many women who have to think about that. But even though I have that privilege, my life is still attached directly to that of my husband’s and the larger family. What I say, write and do affects them all. That responsibility can get heavy, and I have to have all sorts of answers ready should I be interrogated. A long time back at a writers’ meet in Chitwan, author Neelam Karki Niharika asked me how I was doing. In that moment, I was compelled to tell the truth: I told her that I have arrived at the writers’ meet with only half my heart. In that way, all these literary engagements and even my own writing, I can tend to them carrying only half of my heart.

Read also: Factory of Questions: Sarita Tiwari, Muna Gurung

M: Why write, then?

U: Because it is a beautiful excuse to live. It is a form of meditation for me, and even an antidepressant in many ways. When I write I am completely focused in the world of my story; I leave all other worlds behind. To write for fame, money or anything else other than for one’s own self-satisfaction is a mistake. At the end of the day, we just want to be happy. And to write to be remembered? I don’t know, who remembers anyone these days?

Lightroom Conversation is a monthly page in Nepali Times on interesting figures in Nepal’s literary scene. Muna Gurung is a writer, educator and translator based in Kathmandu (munagurung.com).

Read also: Nibha Shah: Nepali poetry's mansara, Muna Gurung

I, Cleopatra. Creation’s Beautiful Mistake

Translated by Muna Gurung

Pour bottles of curses into my soul

Spill bottles of accusations

over my heart

I, Cleopatra, will drink the disrespect

I, Cleopatra, will drink the disgust

I, Cleopatra, will drink the disdain

Like an expert, with ease

I drink my pain down with bottles of alcohol

Like an expert, with ease

I drain my worries into its intoxication

Please continue pouring

an endless stream

of alcohol into the opening

that is my mouth

Please continue emptying

bottles of alcohol –

in a steady stream

lifting the lid of my chest

Perhaps you will get tired of yourself, but

I will never tire

Perhaps you will lose with yourself, but

I will never lose

I am found guilty with the taste of alcohol

I am wounded in its intoxication

I salute cocktail parties

I kiss bottles of alcohol

I am in love with the merry sounds of “Cheers!”

My eyes don’t want to look

at the laughter of society

My ears don’t want to understand

the languages of society

I am a dishonour to the eyes of society

I am an example for the gossip of society

I am an explosion in the secrets of society

I am a rebel against the beliefs of society

I am a criminal in the laws of society

I am a beautiful mistake in the creations of society

writer