Invest in investment

Let us just say, for the sake of argument, that Nepal has now untangled its politics, formed a Constitution, the war is over and there is political stability. (We know that this is not strictly true, especially since there is a disgruntled faction of the ruling party that is on a violent extortion spree across the land.)

Read also: Maze

But suppose we had sorted out the politics, and we were actually taking a big leap forward towards a ‘prosperous and happy’ nation. Would that finally convince foreign investors that Nepal is an attractive place to do business because of its sizeable domestic market and prime location between the world’s biggest markets?

Not really. Foreign investors would look at lists like the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business, Forbes Magazine's Best Countries for Business, or the Global Finance magazine's list of Top Countries for Foreign Direct Investment, and see that Nepal scores nowhere near the top 50, or even the top 100 countries.

Read also:

Nepal, Inc., Suman Joshi

Just Google "Nepal" and "Corruption" and see how low Nepal ranks in the Transparency Index. There is the recent case of the Malaysian telecom investor Axiata being forced to pay Rs61 billion in capital gains tax even though it is the buyer, not the seller, that should be liable. In this space we recently recounted the horror story of how senior bureaucrats repeatedly extorted an Italian contractor for kickbacks and forced its personnel to abandon the nearly complete $500 million water supply project when they did not fork out Rs50 million. A Spanish contractor upgrading Kathmandu airport quit after being harassed over payoffs. Other investors have reported being asked for a cut to repatriate profits, and renewing business visas has become an ordeal. Kathmandu’s air pollution and poor quality of education are other deterrents for investors.

Given such sleazy behaviour, it is surprising there are still foreign companies interested in investing in Nepal. Despite the country’s strategic location, great potential for energy, agriculture and infrastructure projects, the level of foreign direct investment (FDI) has been dropping rapidly.

Read also:

How Nepal can invest in improving the investment climate, Anil Chitrakar

It rose steeply after the Foreign Investment Act of 1992 and the first Investment Summit a year later. But inflows dried up during the war years as the Maoists targeted domestic industries and foreign investors for extortion, threats and bombings. After the end of the conflict, investment rose sharply again as private hydropower projects got underway. However, there has been only $400 million in foreign investment in the past five years, with only $169 million in 2018 since the Nepal Communist Party took office -- a further drop of 15% compared to the previous year.

In the meantime, other developing countries in the region, even those governed by communist parties like Vietnam and Laos, have moved up the value chain in garments and manufacturing and are now attracting investments in energy and electronics. India and China have attracted their diaspora to invest in the home country, but Nepal’s laws have failed to meet the demand of overseas Nepalis for special provisions to non-residents.

Why is Nepal stuck? It boils down to poor governance, lack of accountability, and no rule of law. Those conditions are linked to political will, a national vision and efficient implementation of policies – all in short supply.

This is why, despite being optimistic about Nepal’s long-term future, we are pessimistic in the short-term as the government holds another Investment Summit for the sake of a summit without even beginning to address the root causes.

In the run-up to the Summit, the government hurriedly passed FITTA which actually makes it more cumbersome to get approvals, and has added dairy and agro-industries in the negative list to protect domestic businesses. The Public-Private Partnership and Investment Act, although streamlining IBN’s role, does not address the confusion over jurisdiction of federal and provincial governments. The new rules for hedging on dollar-rupee fluctuations are unlikely to reassure foreign investors because they come with so many if’s and but’s.

Foreign investors are attracted to put money in a country if there are incentives, facilities, transparency, and a guarantee of no bureaucratic harassment. With so much competition in Asia, and especially in the immediate neighbourhood, it is unlikely that many of the 600 potential investors from 38 countries who are in Kathmandu this week will be convinced.

It is hard to entice foreign investors to the country when even Nepali businesses are so hesitant to start up a business. We do not need any more speeches; Nepal first needs to improve governance and transparency before another futile attempt to woo investors.

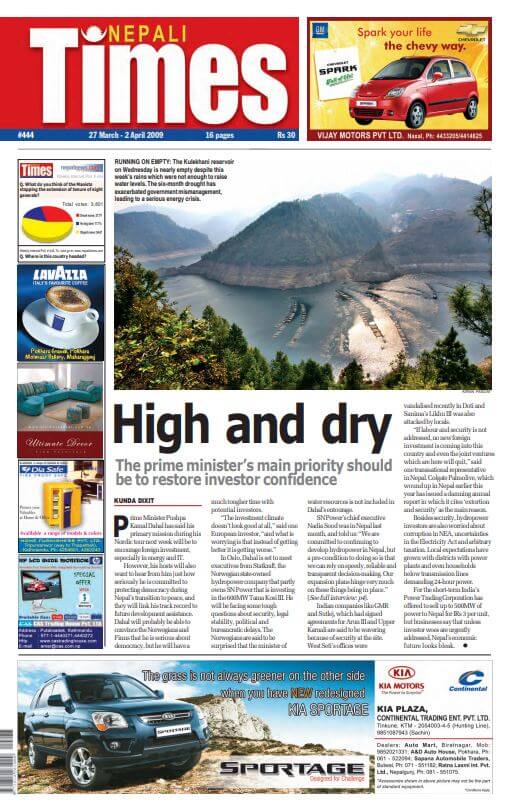

10 years ago this week

Nepal is holding another Investment Summit this week, exactly ten years after Maoist Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal embarked on a trip to Nordic countries to restore investor confidence after the war. Excerpt from a page 1 report in the issue #444 of 27 March – 2 April 2009:

Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal has said his primary mission during his Nordic tour next week will be to encourage foreign investment. However, his hosts will also want to hear just how seriously he is committed to protecting democracy during Nepal’s transition to peace, and they will link his track record to future development assistance. Dahal will probably be able to convince the Norwegians and Finns he is serious about democracy, but he will have a much tougher time with potential investors.

“The investment climate doesn’t look good at all,” said one European investor, “and what is worrying is that instead of getting better it is getting worse.”

In Oslo, Dahal is set to meet executives from Statkraft, the Norwegian state-owned hydropower company that partly owns SN Power that is investing in the 600MW Tama Kosi III, and will face tough questions about security, legal stability, political and bureaucratic delays.