Biplanes and balloons over Mt Everest

Let’s let our imagination soar during lockdown and remember those reckless men in their flying machines

The early 1930s were an era of aviation achievements when Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, Richard E Byrd reached the poles and Amy Johnson flew solo from London to Australia. Experimental flights were attracting not only swashbuckling, pioneering pilots, but also nationalistic sponsors keen to advance technology and force new scientific frontiers.

This month a new biography is published about Lucy Lady Houston, a former chorus girl notorious as the richest woman in England who brushed aside scandal to become the patriotic financier of the first flight over Mount Everest, backed secret military research, and funded the creation of the Spitfire aircraft.

Still nobody had flown over the highest point on earth, and the British were galvanised into action to beat their European rivals. Supported by the Royal Air Force, Britain had the advantage of a newly developed supercharged engine (the Bristol IS3 Pegasus) in a uniquely modified aircraft with an open cockpit they named the Houston-Westland, recommended by the RAF as the fastest-climbing two-seater aircraft ever tested. Douglas Douglas-Hamilton Marquis of Clydesdale (later 14th Duke of Hamilton) was appointed chief pilot, seconded by Flt Lt David McIntyre, each accompanied by an observer cameraman.

Shipped by sea in crates to Karachi then reassembled, the two small Westland biplanes flew to the expedition base at Lalbalu airfield near Purnia in Bihar, due south of Biratnagar and some 160 miles southeast of Everest. The team was joined by three De Havilland Moths which had taken one month to fly out from UK, and large amounts of support equipment.

After all the preparation, by 3 April 1933 the clouds had dispersed and they were ready to meet the unknown challenge of flying over Everest. Climbing from the plains of India to an altitude of 34,000 feet over Nepal, the tiny planes’ double wings delicately bound together with struts and stays were dwarfed by the towering Himalaya. Buffeted by severe wind currents and air bumps, blown sideways off course, dogged by downdrafts and faulty oxygen flows, then saved from collision with icy rock faces by fortuitous updrafts, the two aircraft eventually scraped over the top of Everest, before circling safely back to Purnia.

Lord Clydesdale would never say how close he came to hitting the mountain other than to admit that it had been “cleared by a more minute margin than I cared to think about, now or ever.”

But the first ever Everest flight had failed to collect the expected survey data and film footage because the photographer was unconscious with hypoxia, slumped on the open cockpit floor when his air hose split. After a test flight around Kangchenjunga, one aircraft got lost and was forced to land at a busy railway station to ask for directions home.

Determined to complete their mission, a second Everest flight was made two weeks later on 19 April 1933 to collect the missing data. It had to be undertaken in great secrecy by the defiant aircrew, as it was expressly against the orders of the team leader, sponsor Lady Houston and insurance company who all felt enough had already been risked.

Despite so many close calls, the expedition was hailed as a resounding scientific and technical success, although they failed to detect any traces of disappeared climbers Mallory and Irving. Having captured the first images of the roof of the world with several passes over the peak, their closely guarded pictures helped inform British Everest endeavours, culminating in Tenzing and Hillary attaining the summit 20 years later.

The story is told in a couple of black and white documentaries Wings Over Everest in all its colonial, pith-helmeted splendour, and First Over Everest, giving due credit to ‘His Highness the Maharaja of Nepal within whose territory Mount Everest stands’.

Eighty years later Douglas-Hamilton’s grandson, Charles, retraced the maiden trip – we marked the neglected anniversary with a ceremony at the Nepal Tourism Board in 2013. The BAe Systems official who came with Charles confirmed that the ground-breaking 1933 Everest flight “had led directly to refinements in aviation technology that allowed high altitude flights”.

******

A couple of generations later, cameraman Leo Dickinson is another adventurer who likes to push the limits, pitting a fragile flying machine against the mighty mountains, and specialising in ‘filming the impossible’.

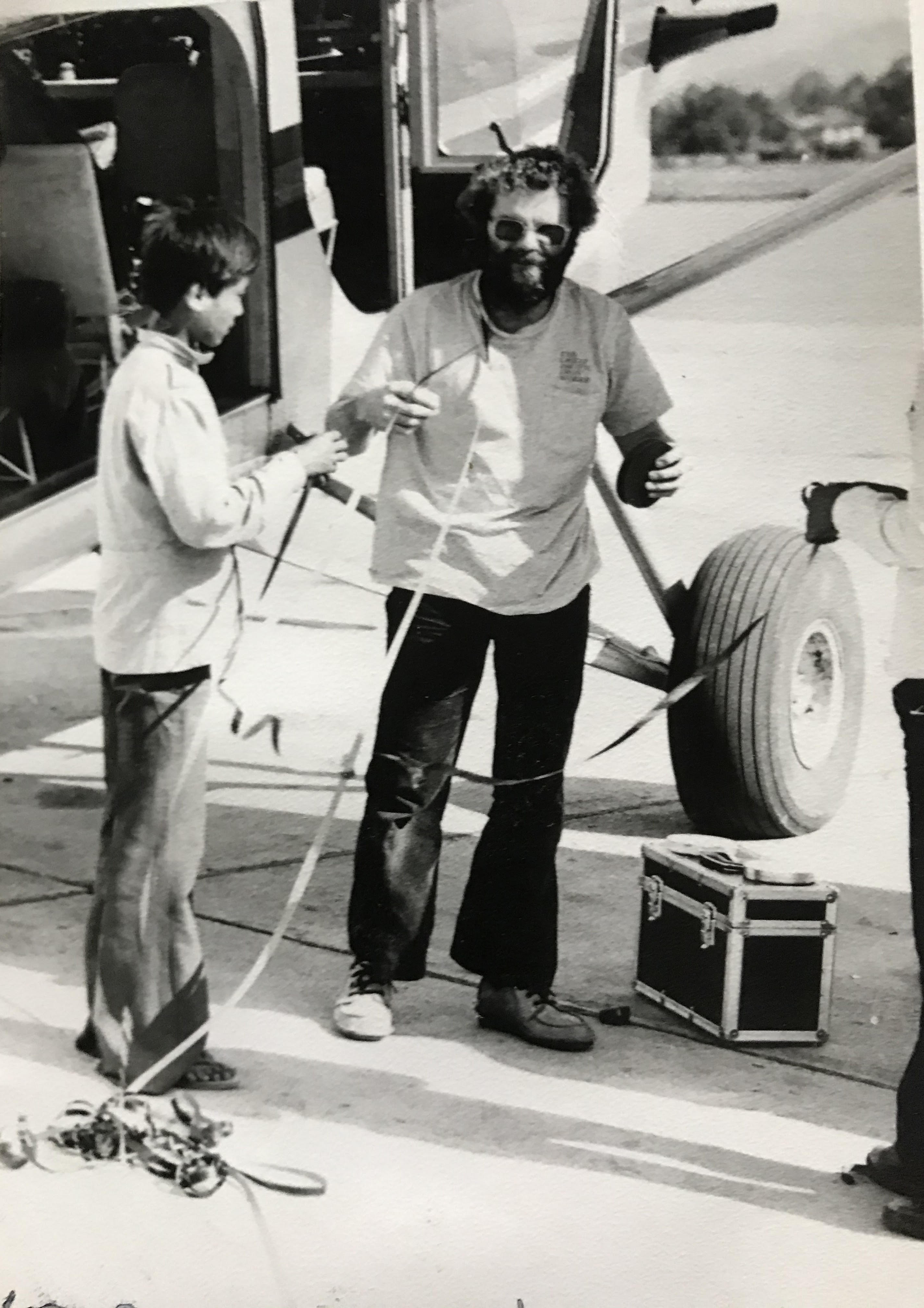

He also enjoys a good joke. Short, bearded and sprightly, Leo danced around the Pilatus Porter plane, a tangle of celluloid film at his feet: “Quick, quick, kick it into the shade before it gets overexposed” he joked. Another one was “On this expedition we are experimenting with freeze dried water.”

This 1991 expedition was aiming to fly a balloon over Sagarmatha, and we were tasked with helping with their Nepal support logistics. The four members consisted of adventure afficionados led by Leo with pilot Andy Elson, mountaineer Eric Jones and stroppy Aussie veteran balloonist Chris Dewhirst. They remain the first and only hot-air balloons to have flown over Mt Everest.

Chris and Leo had made an earlier unsuccessful attempt to balloon over Everest in 1985 with an unruly bunch that had led to near-disaster. The team trained in skydiving in case of having to bail out, sought astrological predictions and practiced with flights at Bhaktapur and Bodnath.

On the actual flight, they used fuel too fast, failed to gain more than 26,500 feet altitude and were forced to abort ten miles short of Sagarmatha. One balloon crash-landed into a tree and the other spread across a hillside before catching fire. Still, it stood as the highest alpine ballooning flight in history at that time.

A crew of three Japanese attempted to fly over Everest from the north side in 1990 but smashed their balloon into the side of a cliff, lucky to escape with their lives.

Leo and Chris were keen to complete their abandoned traverse of the world’s tallest mountain. The logistics to fly from the Khumbu over Everest to the Tibetan plateau were complex, requiring unprecedented Nepali-Chinese permissions, and an army of porters and yaks to ferry the fuel cylinders, camera gear, and snaking balloon skins. After Buddhist blessings at Tengboche, they set up their own weather station at Gokyo to measure the jet stream whilst meteorological satellites monitored the mountain’s moods.

Acclimatisation was an important part of preparation whilst awaiting perfect weather conditions, but rivalry amongst the leaders was causing rifts and threatening competition instead of cooperation for the daunting exploit ahead.

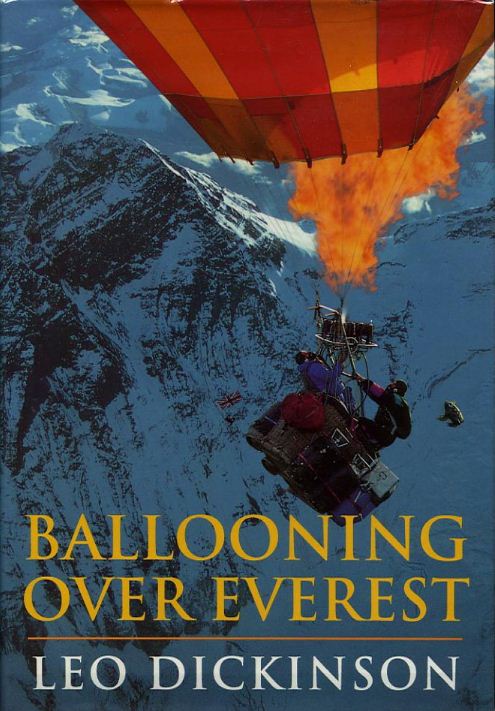

When the two balloons finally took off from the sacred shores of Gokyo lake trailing prayer flags and waving to locals, support crew and girlfriends, Leo was perched on a camera platform outside the basket. “Chris’ ego means there is no space for me inside,” he quipped.

The wind carried them up and away, whizzing past the shimmering summit of Sagarmatha at 100 miles an hour with Leo’s suspended cameras capturing the unique perspective of the highest Himalayan landscape spread beneath their frail wicker baskets.

The expedition goal had been achieved, but technical problems were only just beginning. Communications collapsed, Chris jumped the gun, both balloons got separated soon after take-off, and the hot-air temperature was running too high, threatening to rupture the membrane. Gaining altitude, hypoxia affected all of them even with oxygen masks and, despite the additional canisters lashed to the baskets, they again burned fuel faster than anticipated.

Andy and Eric suffered the deadly silence that every balloonist dreads when the burners fail and everything goes out. With not enough oxygen in the atmosphere to keep the vital burners going, in order to reignite the pilot-light they had to balance on the basket rim with a box of matches.

Out of gas and spinning like a top, Chris was forced to make an emergency landing, crashing down in Tibet and being dragged across two miles of rugged rocky terrain. The flimsy balloons, expensive equipment and Leo’s cameras were in smithereens, but the film survived as a classic Everest by Balloon.

It was left to our colleague, mountaineering operator Russell Brice, to pick up the pieces on the northern side in Tibet – Leo had broken ribs, all were badly shaken, and everyone agreed it was a miracle they survived. The voyage had proven that the extreme altitude and climatic dangers of flying hot-air balloons in the high Himalaya were so enormous that no one has been reckless enough to attempt the feat since.

writer