Nepalis queueing up all night for proof of jab

Vaccine certificates are just another in a long checklist of permits and authorisations for Nepali workers headed overseas

After getting his single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine, Yogendra lined up the following morning from 2AM at Teku to get his vaccine certified so he could go to Saudi Arabia to join his job. But his letter was missing a stamp, and he had to return the next day.

Like Yogendra, thousands of workers have packed queues at the Teku Hospital to get their certificates, with fears that the crowds could themselves spread the virus.

“There is a lot of mixed information and confusion, and the officials do not seem to know what to do,” says Yogendra. “And how can we be safe in these crowds?”

Yogendra said “cautious goodbyes” to his family in Doti and travelled to Kathmandu, not sure if he could finally leave. Distressed and demoralised, he has had to spend more money extending his stay to finish his paperwork.

Netra from Jhapa is also going to Saudi Arabia, and got to Teku Hospital only at 6AM by which time there was already a long line, and he had to go back.

“Tonight, I will come at 9PM so I am one of the first ones in line,” he told me. “Even 2AM might be too late.” For Yogendra, Netra and many other workers getting ready to leave, it is difficult to get around in unfamiliar Kathmandu and work the system to get all the required travel documents. “My legs are sore from all the walking and standing,” says Netra.

Akram (pictured above) from Sunsari did not want to take any chances, so instead of lining up at 2AM for his vaccine certificate, he was already at Teku at 4PM on Saturday to be in front of the line for Sunday morning.

After getting his jab last week, he came to Teku twice, but missed his chance to get his certificate both the times because he came only at 6AM. This time, he was waiting 28 hours before the counter opened.

Akram is headed to Qatar to work as an office cleaner and will be earning $360 a month. This is his first time in Kathmandu, and he slept on and off all night while squatting under a tin roof to keep dry in the rain.

The security guards at Teku took to Akram for his determination and grit, and they had given him a nickname: ‘Number One’. By 10PM on Saturday, Akram had been joined by others who also wanted to be ahead on the line.

Among them was Gopal Thapa Magar from Ramechhap bound for Saudi Arabia, and a returnee migrant Dinesh DC from Dang. The three bonded while waiting, and took turns to have tea in a nearby shop as they waited for dawn to break.

From Sunday, to prevent overcrowding in Teku, the government will provide vaccination certificates from four hospitals in Kathmandu.

For Nepali migrant workers, the vaccine certificate is just the latest in a long checklist of permits, certificates and authorisations to complete.

But such is the desperation because of the lack of job opportunities at home during the pandemic that despite the harrowing obstacles, workers like Yogendra, Netra and Akram cannot wait to leave.

For the first time in two decades, the number of annual labour approvals fell below 100,000 to just over 72,000 in 2020-21. This drop reflects the shrinking opportunities for Nepali job seekers who have relied on migration to break out of intergenerational poverty.

The reasons for the historic low numbers are fallout from the pandemic and continued hiring freezes and travel bans to some countries. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE accounted for 80% of labour approvals in 2020-21, while few workers went to Malaysia and Kuwait which had consistently been among top destination countries for Nepali overseas workers.

Malaysia halted recruitment of all foreign workers indefinitely since early last year, while Kuwait red-listed Nepal for public health reasons since the early days of the pandemic until recently.

The drop in annual outflow of workers paints an incomplete picture: nearly 500,000 Nepali workers were repatriated from all over the world with majority from Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia in the past year. And a significant number of Nepalis abroad chose to stay on their jobs.

However, there are no reliable estimates of the total number of Nepalis working overseas. According to Malaysian government data obtained by Nepali Times, the total number of Nepalis there dropped from 300,000 at end-2019 to just over 160,000 in 2021. But this excludes undocumented Nepalis in Malaysia, whose numbers have grown significantly since the pandemic.

Employers there have been hesitant to send back workers due to worker shortage and hiring freeze, delays in receiving exit permits or because of unaffordable tickets.

Since migrant workers do ‘essential’ jobs, there is still demand for them in certain sectors. Recovery of emigration will require Nepal to be more strategic about exploiting these constricted opportunities.

For example, despite many job opportunities in Saudi Arabia, recruitment has been affected over the past year because of delays or temporary obstructions in ‘demand attestation’, a mandatory requirement in the recruitment process. Similarly, embassies accredited to countries like Turkey, Poland and Croatia have also not been proactive about demand attestation.

For European countries where there are delays with job demand letter approvals by Nepali embassies, the share of workers obtaining individual labour approvals instead of institutional approvals is high even when the recruitment is facilitated by recruiters.

This means recruiting agencies cannot be held liable in case of problems with the worker’s contract or safety. Misuse of approvals can be costly because recruitment costs are high for these countries, aspirants are easier to lure and European countries are fertile for trafficking.

With Covid-19, maintaining a balance between facilitating recruiters to play a critical intermediation role with regulatory actions to curb malpractice and exploitation of desperate job seekers has become even more challenging.

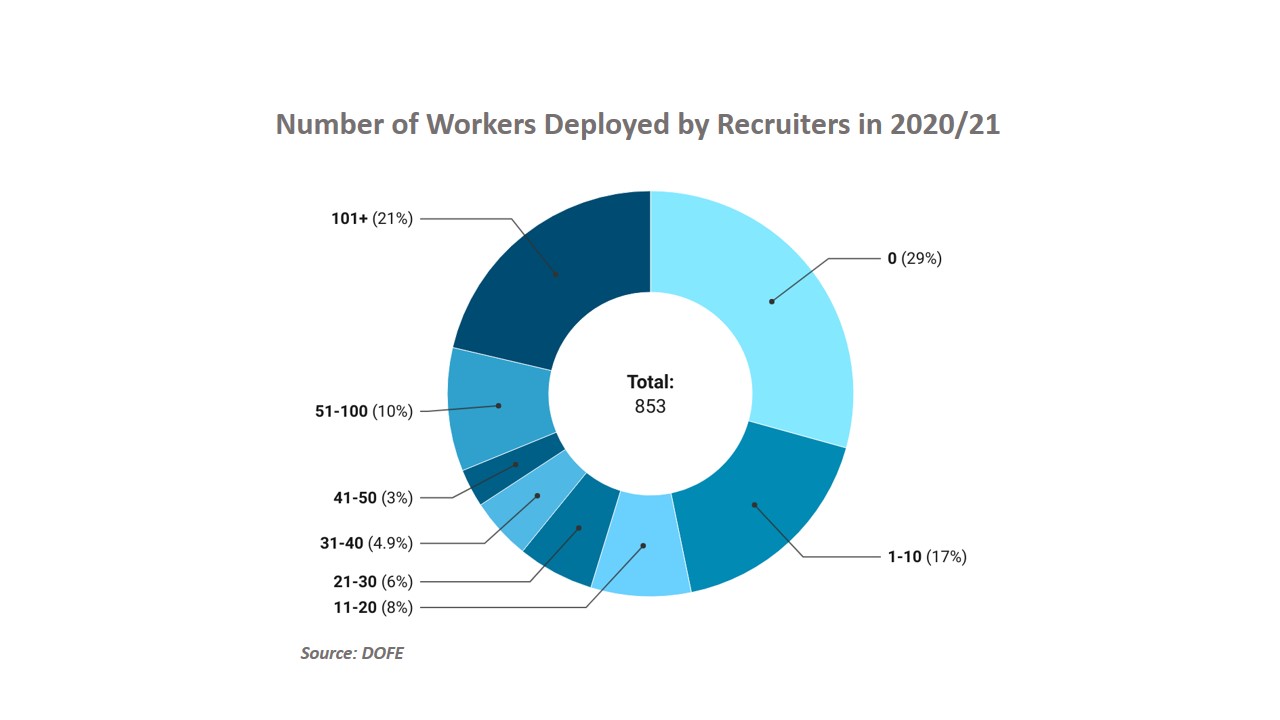

Recruiters complain that the government has not acknowledged their contributions or the impact of Covid-19 on their businesses. Last fiscal year, almost a third of the 853 recruiters in Nepal were unable to obtain labour approvals for a single worker, while about a fifth deployed less than 10 workers over the entire year (See figure).

While regulation is necessary, it can sometimes unreasonably inconvenience the employer, recruiter or migrant worker without addressing, or correcting the problems. In many cases, regulations create loopholes to worsen the safety and welfare of migrants.

For example, attestation of employment demand letters is a welcome move to curb fraudulent job orders which now needs to also scrutinise employers’ commitment to Covid-19 health protocols.

But its effectiveness rests on proactive embassies to carry out the attestation services of rewarding job orders expeditiously and fairly. Otherwise it prevents gainful employment, or worse, compels migrants to bypass the legal system.

Recruiters have not been able to smoothly deploy workers to Qatar. The Qatar Visa Center (QVC) was set up as a ‘one stop’ window to facilitate medical tests and biometrics, but is accused of lack of transparency. In the past, a handful of medical centres approved by the government could be used for the pre-departure medical tests.

Now, QVC alone cannot keep up with applicants and the backlog from the lockdown months, impacting over 7,000 Qatar-bound Nepalis, says Sujit Shrestha of NAFEA (National Association of Foreign Employment Agencies).

The QVC management has been accused of providing appointments selectively to well-connected manpower companies. “If we take an appointment in July, we get dates for September and October,” says Shrestha. “How can we work like that when Qatari employers are in a hurry to recruit workers to complete their projects delayed during the pandemic?”

Nepali and Qatari authorities need to investigate these allegations against QVC and ensure it operates as intended.

The latest is the challenge of vaccination. Inconsistent vaccines requirement, authenticity of vaccine certification and wide availability of vaccines have been problems. The J&J Janssen jabs are ideal for migrant workers because a single dose saves outbound migrants time, and it is recognised by destination countries -- unlike the Chinese jabs that are not accepted in countries like Saudi Arabia.

Furthermore, the J&J jabs exempt migrants from expensive institutional quarantine in destination countries. But it has come at a cost as reflected in Akram’s experience. Shrestha of NAFEA says that it would have been much easier if, like other countries, vaccine certificates had a unique QR code for authentication.

Major destination countries have launched their own mobile apps that will be used mandatorily including to enter public spaces and workplaces. There is uncertainty about the acceptability of paper-based vaccine documents that are being given out in Nepal.

“This has to be a continuous effort, not a one-off initiative, with dedicated vaccination camps for migrant workers that will also involve DOFE officials so workers with jabs get certification as well. Everyday hundreds of migrants will require jabs, and there is no clear policy for them,” Shrestha says.

The uncertainty and lack of coordination in the vaccination drive has financial and time costs, but there is also the invisible mental toll it takes on workers wanting a better shot at life. Nepal needs better labour diplomacy, inter-ministerial coordination and most importantly, empathy for migrants.

The Labour Ministry is currently without a minister in the new government, and over the course of the pandemic there have been four Labour Ministers, including the last two who were in office just for a few days.

Despite all this, remittances have so far defied expectations. Nepal Rastra Bank data for the past 11 months show that remittance saw a 12.6% increase to Rs871 billion compared to 2020-21, but a 3.2% increase compared to 2019-20.

We are quick to celebrate the resilience of remittances amid a pandemic and migrants as ‘heroes’, when they are the first ones abroad to send us oxygen cylinders and medical supplies.

Om Thapa and Niraj Lama helped with reporting this story.

Upasana Khadka writes this column Labour Mobility every month in Nepali Times analysing trends affecting Nepal’s workers abroad.

writer