Climate of tragedy and apathy

Nepal’s inability to raise Himalayan haze and permafrost issues at COPs and regional fora exposes failures in science and diplomacyYou do not have to be a climate expert or atmospheric pandit to claim that Nepal is not pulling its weight on the grand narratives of the Anthropocene. As a heavily populated ‘country-on-an-incline’ from the Tarai to the Himalaya, Nepal is a thermometer of global warming.

Its people are human witnesses to environmental and climate breakdown, but remain mute observers to the unfolding crises. Nepal should be leading the pack at the COP30 climate conference in Belém, backed by science and lived experience.

But it is doubtful that two of the most crucial climate-related subjects central to the culture, economies and human wellbeing in the Himalaya and South Asia will be discussed at the summit that started this week in Brazil.

The first topic that should be raised at COP is Black Carbon or the South Asian Brown Cloud, made up of tiny suspended particles in the air. This is not just a transboundary health hazard, there is now enough science to make the case that Himalayan snowmelt is accelerated significantly by the albedo effect that makes ice melt faster because of reduced reflectivity.

But Kathmandu has not been able to make governments near and far listen. In 2014, I wrote a short piece published in Outlook magazine explaining why India’s Prime Minister Modi looking northward from a SAARC Summit retreat in Dhulikhel was unable to see the Jugal Himal range barely 30km away.

His view was obscured by the pollution layer arriving from as far away as Lahore with substantial contribution from the Delhi region. That summit itself was an opportunity for Nepal to inform the Indian and Pakistani prime ministers that much of the haze, smog, dust and soot that settles on our slopes was generated in Sindh, Punjab, Punjab, Haryana, Western UP and Delhi NCR, carried by prevailing westerly winds up to the Himalaya.

The forest fires within Nepal as well as Kathmandu Valley’s pollution contribute to the haze, but the shroud that suffocates the region through autumn, winter and spring is mostly transnational. Last year, these anthropogenic fine aerosols actually curled over the Bay of Bengal and invaded the airspace of Sri Lanka and Maldives.

Even as the soot particles accelerate glacial melt and impact everything from infrastructure to public health, the most visible effect is on tourism. Nepal’s economic future is based on tourism, and much of this relies on being able to see the snow mountains. Why should travellers go to Pokhara if they cannot see the Annapurnas?

Hoteliers in Nagarkot have started a campaign: ‘Visit Nagarkot 2025: More than Sunrise and Sunset’. While clever, the slogan is a response to the acclaimed Himalayan vista from Everest to the Annapurnas from the hill station, now obscured by the brown curtain of haze for most of the year.

As the bellwether country of South Asia when it comes to the climate crisis, Nepal must build diplomatic confidence to reach out to the governments of Pakistan and India even in their present state of antagonism. Kathmandu must launch ‘haze diplomacy’ for its own sake and for the region.

IMPERMANENT FROST

Permafrost is understood mostly as a phenomenon of the Arctic, Antarctica, Siberia and Alaska. Mountains elsewhere did not figure, though it was natural for the ground to freeze all year round at high altitudes.

In the Himalaya, besides the snowfields and glaciers, frozen moisture binds rocks and stabilises slopes. But global warming is melting the permafrost that used to cement mountain flanks, including boulders, sand and scree slopes. Some of the debris (गेग्रान) did tumble down, but much of it remained entombed on high, thanks to permafrost.

Pokhara Valley and the Seti River reaching all the way up to the base of the Annapurnas, is the best place to observe this dance of geology between gravity and the mountain range.

Rubble from the collapse about 700 years ago of paleo-Annapurna IV created the sediment field on which Pokhara is situated today. However, much of the debris from the crumbled mountain is still lodged up on and around Annapurna IV, but the binding is loosening with the warming earth.

A 2024 report by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) indicates that global warming is thawing the permafrost across High Asia. Among the unintended consequences of climate breakdown is that mountains and moraines are collapsing, with cascading impact that includes glacial lake outburst floods, reduced groundwater recharge as well as winter flow in the Ganga, Indus and Brahmaputra.

No one has calculated the total volume of rubble locked in by permafrost across the Himalaya. Despite the increased risk, there is accelerated construction of highways, hydropower projects, housing and tourism infrastructure across the Himalaya. While the COP conferences discuss rising oceans and receding glaciers (without doing much about it), Himalayan permafrost has been melting unremarked.

In their path-breaking September 2024 article in Nepali Times, Wilfried Haeberli and Alton C Byers argued that the extreme events of the past few years that led to mountain and moraine collapses, unleashing destructive debris flows downstream, were the result of melting permafrost.

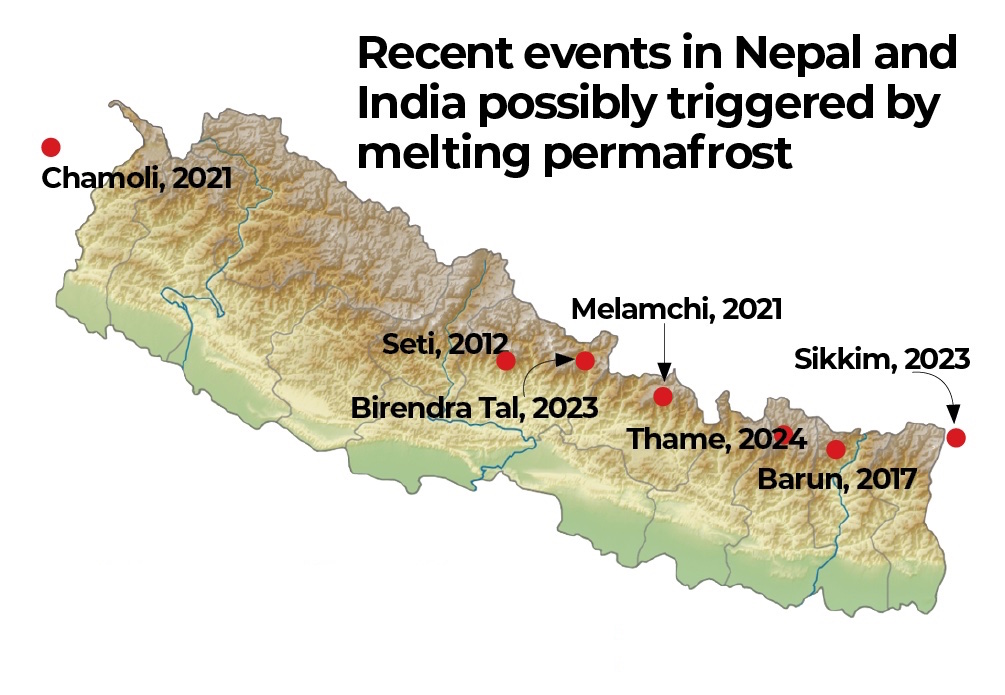

Haeberli and Byers suggest that the avalanches and floods including those of Seti (2012), Chamoli (2021), Birendra Tal (2023), Sikkim (2023), Thame (2024), Barun (2017) and Melamchi (2021) were the result of the thawing of frozen ground.

They say that the collapse of the lateral moraine on the South Lhonak glacial lake in Sikkim on 4 October 2023 that swept away more than 100 people, destroyed the $1 billion Chungthang Dam as well as houses, roads and farms far downstream, was also caused by cloudburst on a lateral moraine that had lost its permafrost adhesive.

There will be permafrost sceptics, as there have been climate change deniers. But it is time to wake up to the reality that the Himalayan peaks are no longer the immutable sentinels as regarded by humanity since prehistoric times.

Modern society has pumped so much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere that now even the mountains are giving up. And we have not even begun to think about the bacteria and viruses locked away in the permafrost up the slope.

Loss of permafrost adds to the cumulative impact of climate breakdown, including extreme weather events, drought and cloudbursts, heat waves in the plains affecting lives and livelihoods, creating mass migration, social unrest, and upending politics and geopolitics.

The government and polity of Nepal have a duty to themselves and the larger humanity to wake up to the climate breakdown. The Sagarmatha Sambaad conclave organised by the Government in May failed to emerge as a pulpit for global warming and associated ills. Our political class, bureaucracy and academia should make up for lost opportunities to rise to the occasion and take the lead.

Kanak Mani Dixit is writer, commentator and founding editor of Himal Southasian.